The waves That Changed Us

On the morning of Dec 26, 2004, tectonic plates collided. The resulting 9.1-magnitude quake raised the seafloor so significantly that it lifted the global sea level by an estimated 0.1 of a millimetre.

More than 30 cubic kilometres of seawater was displaced. That volume of water would fill 12 billion Olympic-sized swimming pools.

More than a dozen countries including Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, India and Sri Lanka were hit. Over 230,000 people died.

The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami had made its devastating mark on humanity.

Twenty years on, affected communities are still picking up the pieces of their lives and livelihoods.

The CNA team that returned to ground zero for the documentary The Waves That Changed Us, which aired its four episodes between Dec 22 to 25, share what they saw and heard on the ground during their time there.

Rahmatullah Mosque in Lampuuk gained global recognition through the striking images of its white facade juxtaposed against the scarred dirt landscape.

Some attribute its survival to divine intervention, but a more likely explanation lies in its design - its first floor had only columns and no walls, allowing the torrent of water to pass through.

Inside, remnants of the original mosque have been preserved, left untouched as they were 20 years ago, serving as a poignant reminder of the disaster.

Syiah Kuala University

So if the water enters from here, it just flows through.

Because this mosque is very close to the beach, the waves weren’t carrying much debris.

Maybe if the mosque wasn't close to the beach, there would be a lot of debris that the waters would bring and maybe then it would collapse.

Ironically, the mosque has since been enclosed with walls, sealing it into an air-conditioned space.

If another tsunami hits, flood waters will no longer be able to flow through it.

In the haste to rebuild, many buildings across Aceh were constructed with little consultation with local communities and often at high cost. Professor Nazli Ismail from the Department of Geophysical Engineering at the Syiah Kuala University in Aceh, feels that if this dialogue had taken place, money could have been saved.

A new facade was built over the original mosque.

In the aftermath of the tsunami, evacuation buildings and routes were mapped out and built.

While the evacuation buildings are important structures, they remain voids within communities and serve very little purpose other than in times of emergency.

Prof Nazli suggests that with better cultural understanding, evacuation centres could have been integrated into mosques during construction.

After all, Acehnese instinctively know to head to a mosque in times of trouble. The people here are deeply religious. It’s even been claimed that Islam first arrived in Indonesia through Aceh.

Changes in infrastructure are not the only sign of change in Aceh, a place that is famed for its coffee.

Solong Coffee in Ulee Kareng is one of the most famous coffee shops in Aceh.

In the past, only men were seen in coffee shops.

Not only were women not seen in coffee shops, it was also culturally not acceptable for women to have a “visible” public job or be out at night.

But the 2004 tsunami also resulted in a change in the fabric of society in Aceh.

With the post-tsunami influx of international aid, foreigners came to help and, with them, new ideas and influences.

As Aceh was reborn, a cultural shift took place.

The tsunami, while tragic, opened up Acehnese society, enabling women to participate more actively in public life.

With lush paddy fields that produce more than 40 per cent of the country’s rice, the Malaysian state of Kedah is also known as the “rice bowl of the nation”.

But in the district of Kuala Muda, situated along Kedah’s coastline, the community has for generations relied on the sea for its livelihood. Many here work in the seafood trade.

This symbiotic relationship also meant the tsunami’s destruction was deeply felt here, with many suffering great losses.

When the tsunami crashed into Kuala Muda and neighbouring Penang just after noon on Dec 26, many residents were gathered at Pasar Bisik, the local fish market.

Locals recall hearing the sound of thunder before being hit by two big waves. In the aftermath, 67 people died across the country, out of which nine were from Kuala Muda.

The victims were between 11 months and 74 years old. About 60 houses were destroyed.

It is these ruins that greet visitors to Kuala Muda today. A large cluster of these destroyed buildings has been gazetted by the local government as a heritage site to commemorate the town’s tragic history.

It’s like these houses were frozen in time. You can see features like kitchens and toilets intact. You are immediately confronted with a chilling picture of how the tsunami wrecked households and ordinary lives.

charles phangSeries producer of CNA’s The Waves That Changed Us documentary

Overall, the 700-strong community sustained losses totalling US$3 million. Of this, 10 per cent comprised damage to vehicles such as motorcycles, trucks and boats.

Today, a memorial tower stands at the heart of Kuala Muda.

It is made from broken boats donated by fishermen affected by the tsunami.

Retired fishmonger Ahmad Osman was one who witnessed the tsunami first hand. He saw his fellow villagers drown before his eyes and felt helpless to save them - an experience that still haunts him today.

He also recalls that on the day of the disaster, his son returned home covered in mud and wouldn’t speak to anyone.

In the years that followed, Ahmad, along with many of his villagers, pivoted to new trades and this helped diversify sources of income in the town.

Ahmad himself set up a restaurant at Tsunami Square - a large compound that comprises a museum, a memorial tower and a park dedicated to the victims of the disaster.

We now have new sources of economy in the village. So I feel that the way villagers earn their income today has changed a lot compared to before the tsunami. To me, this means that the tsunami created an opportunity for change.

Beyond the economic changes, Kuala Muda has also seen its physical landscape evolve to include safety measures in the event of another tsunami.

These include a tsunami warning tower, a sea wall and a nearby school that has been designated as an evacuation centre for residents.

But even with these measures, residents remain anxious, having witnessed what nature is capable of.

They cite the stretch of beach behind Tsunami Square as an example. It did not exist before the tsunami, and was pushed out of the depths of the sea during the disaster.

Its very presence is evidence of nature’s ability to reshape reality.

Along the coast of Thailand’s Phang Nga province lies the popular resort town of Khao Lak.

Located about a two-hour drive from Phuket, it boasts clean and tranquil beaches that draw thousands of tourists annually.

It’s easy to forget that more than 4,000 lives were lost here to the Indian Ocean tsunami two decades ago, accounting for more than half of Thailand’s death toll in the wake of the disaster. The majority were tourists.

Most hotels and shops were also destroyed by the tsunami, resulting in about 200,000 locals losing their jobs overnight.

Scenes of devastation in the resort town of Khao Lak, which saw the most foreign casualties in Thailand during the 2004 tsunami.

Since then, resorts and retail spaces have been rebuilt and visitors are welcomed by warmth and smiles that conceal Khao Lak’s dark past.

Reminders of the tsunami are also scant, with the most prominent being a park dedicated to the victims of the disaster.

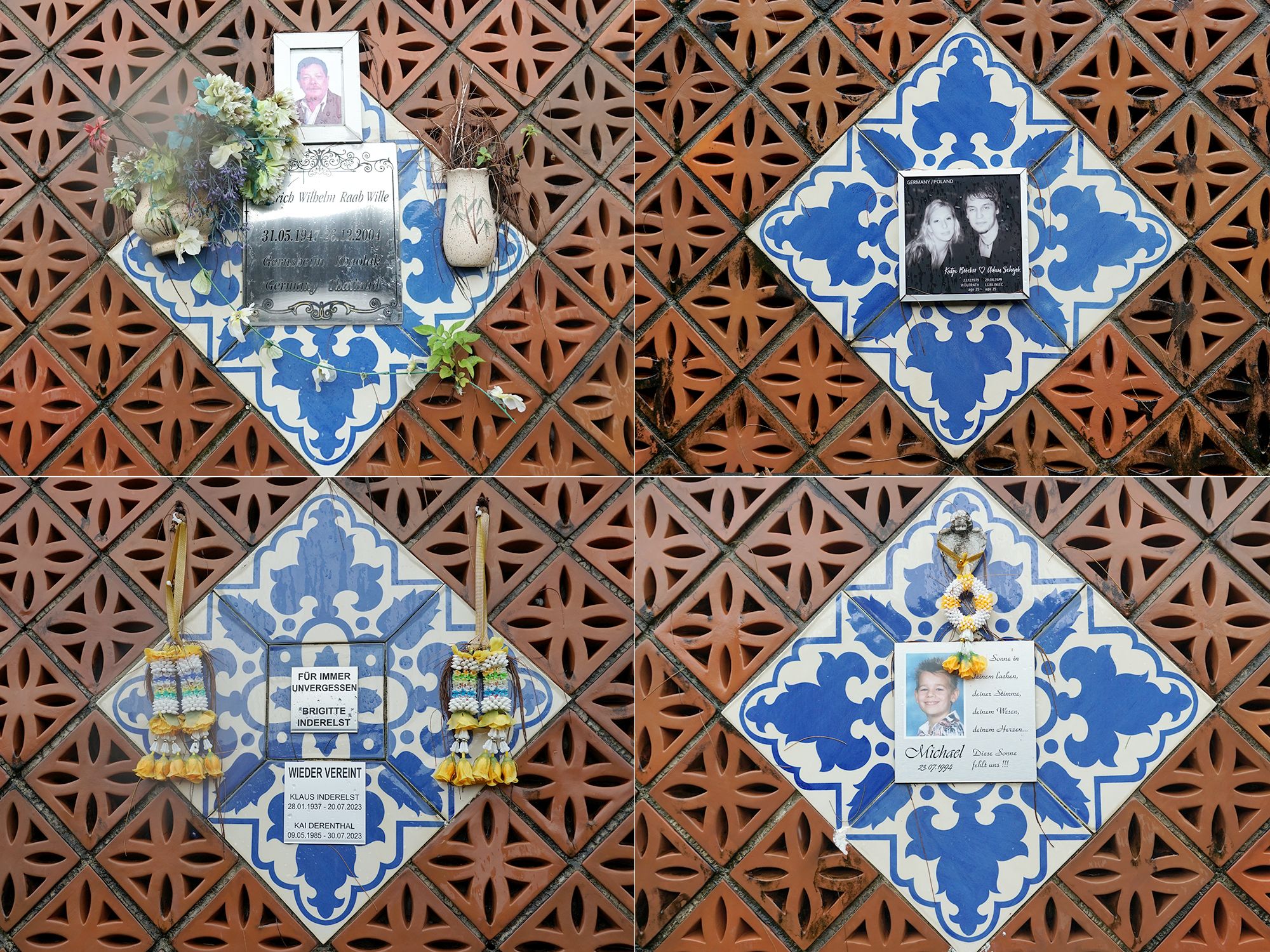

The Baan Nam Khem Tsunami Memorial Park, spanning 8,000 sq m, houses a 100m-long monument made from clay. It’s decked with ceramic tiles bearing the names and faces of 1,400 souls who perished in the giant wave, which the structure was designed after.

Seeing the photos of people from different walks of life and nationalities who were bound by the same tragedy and forever immortalised on the walls of the monument, you can’t help but feel sad. You are gripped with the tragic truth that many of these tourists checked in at resorts here 20 years ago but never got to check out.

charles phangSeries producer of CNA’s The Waves That Changed Us documentary

One of the monument’s visitors is Wimon Thongtae. The fisherman’s daughter, Nong Pim, is one of the many honoured on the walls. She was two.

When the tsunami hit, Thongtae was out at sea. The disaster not only claimed his child, but also his house and half of his village.

It’s hard to explain. It’s like wanting to be close to my child but when I visit the memorial, I am deceiving myself.

I also used to keep photos that the forensic department took of her body. Then, one day I threw them in the trash. The rubbish truck came to collect the trash. I quickly ran to retrieve the discarded photos.

I wanted to forget but it hurts.

Apart from the memorial, a decrepit police boat sitting in the heart of Khao Lak’s town centre is another stark reminder of the tsunami’s imprint on the town.

Former local politician Maitree Jongkraijug says the decision to preserve the boat was to serve as a reminder: If a tsunami were to occur again, people will have to escape further than where the boat lies if they want to survive.

Maitree Jongkraijug lost 40 relatives to the disaster two decades ago.

In the ensuing years, he dedicated his time researching disasters and conducting trainings for locals in his village and other Thai provinces on disaster preparedness.

He educated himself about the Ring of Fire and how it affects Thailand, so that he could teach others how to prepare and respond to its impact.

A key message for Thailand’s disaster preparedness campaigns is teaching locals and visitors to identify their nearest evacuation site and finding the quickest route to reach it when the tsunami warning is triggered.

To date, 150 tsunami warning siren towers and 50 evacuation shelters have been installed across the country.

We don’t want a situation where 50 years later, our generation is gone, and the younger generation does not know about the tsunami. If that happens, our community will suffer the same loss again, should the tsunami return.

The Shrine Basilica of Our Lady of Health in Velankanni, Tamil Nadu, attracts millions of pilgrims to the coastal town every year.

Built in the 1600s, this Catholic church is famous for its gothic architecture as well as miracles that have purportedly been observed within its walls.

How it withstood the wrath of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami can be considered a miracle too.

On Dec 26, 2004, many parishioners had hit the beach after attending Sunday mass.

Church rector, Father C. Irudaya Raj, shares that eyewitnesses claimed the waves made a sudden deviation just before hitting the church, sparing the institution and those in it.

Most who were unable to seek refuge in the church in time did not survive. It’s estimated that about 600 pilgrims died on the beach that day. Many of the bodies were never identified.

India’s overall death toll was over 10,000.

Church clerk A. Jo. Stalin helped to arrange the mass burial for these victims. Its emotional toll still weighs on him today.

I had to carry so many corpses that the images of the dead affected me. Twenty years on, I may have forgotten the details but I remember what I experienced.

Today, the word ‘tsunami’ will trigger a wave of memories and all those horrific images will come back to me.

Another religious monument also weathered the 2004 tsunami.

Built nearly 500 years ago in honour of the revered Sufi saint Hazrat Shahul Hameed, the Nagore Dargah is one of the most sacred Muslim sites in the state.

When disaster struck, it hosted more than 4,000 displaced residents who lost their houses. Across Tamil Nadu, it’s estimated that more than 120,000 houses were lost to the waves.

For the people who came here, we only saw human beings. We didn’t see caste or religion. They had nowhere to go, so the Dargah took them in.

In the wake of the tsunami, the Dargah attended not only to the displaced, but the deceased as well.

Traditionally, Muslim cemeteries reserve their burial grounds for those of their faith but this practice was put aside under such extreme circumstances.

When we buried them, we did it regardless of religion. This is the only burial ground where Hindus and Muslims have been laid to rest together.

Suffice to say, Tamil Nadu was hard hit by the natural disaster. About 80 per cent of the victims were from here and mostly from fishing communities.

Many of the veteran fishermen have been in the trade since they were teenagers.

But in the aftermath, many of them suffered from various forms of trauma, including a deep phobia of the sea.

To help residents overcome their trauma, the local government and unions worked with NGOs to set up a counselling hotline for fishermen. They also arranged door-to-door counselling services.

This helped them overcome their traumas, and more returned to the trade in time.

We were very afraid of getting back into the ocean. I was shivering when I first went back to the sea.

Initially only 10 out of 100 boats in the village went out to sea. Then, it became 20 boats. Eventually, everyone was fishing again.

In the coastal village of Peraliya, 120km south of Sri Lanka’s capital, a railway that passes through the town carries a heavy and tragic history.

On Dec 26, 2004, the Ocean Queen, a train bound for Matara, set off from Colombo just after sunrise. It never arrived at its destination.

Train guard Wanigaratne Karunatilleke, who was responsible for the safety of passengers and cargo, recalls having to make the call to slow the train when the traffic light at Peraliya suddenly turned red.

Looking out the window, he was greeted by an unforgettable sight.

It was like some water overflowed from somewhere. In the flood, I saw refrigerators floating, along with other household items.

I saw a girl floating towards the train, clinging to a fallen tree. There was another boy, about 12 years old, holding on to a gate.

The tsunami inundated several Sri Lankan towns and cities in deadly floods that swept houses, along with its occupants, away.

Karunatilleke saved the two children.

But within moments another wave crashed in. It derailed the Ocean Queen and hurled it about 100 metres away from the tracks.

More than 1,700 people lost their lives in the train wreck. Hundreds of their bodies were never recovered.

The Ocean Queen disaster remains one of the deadliest train accidents in history, and a stark reminder of the tsunami’s devastating impact.

Karunatilleke helped pull nearly a hundred survivors from the wreckage. But he regrets not being able to save more.

Between the first and second wave, we actually had enough time to escape. We could have even gotten away on foot, but at the time, we assumed they were just ordinary waves.

If we had known more about tsunamis, we could have saved many lives.

Elsewhere in Sri Lanka, the district of Hambantota bears the legacy of being the country’s most devastated area.

Over 4,000 locals lost their lives here, making up more than 10 per cent of the country’s tsunami death toll, which stands at over 30,000.

Thousands of people were also displaced.

Many schools in coastal Sri Lanka were destroyed by the tsunami, prompting international NGOs to help rebuild them.

Since then, much of Hambantota has been rebuilt by the Sri Lankan government in collaboration with NGOs.

Apart from rebuilding homes, priority was placed on restoring one crucial piece of infrastructure - education.

Many of Sri Lanka’s schools were destroyed during the disaster. To fill the void, two NGOs - the Singapore Red Cross Society and the Singapore Sinhala Association - partnered with the Sri Lankan government to set up the Sri Lanka-Singapore Friendship College.

Of the Sri Lankans who died in the tsunami, about two-thirds were women.

Many of them were housewives who did not complete high school.

Since opening in 2010, the Sri Lanka-Singapore Friendship College has worked to correct this trend by empowering women through education.

The Sri Lanka-Singapore Friendship College, set up in 2010, is a collaboration between two Singapore NGOs and the Sri Lankan government.

We want to remove the notion that in a home, kitchen work and cleaning are designated for women. We want to move away from that, and see women in leadership.

If there is one positive that’s emerged from this heartbreaking devastation, it is this shift in mindset for female education, as one graduate from the Sri Lanka-Singapore Friendship College attests.

After such a disaster, people felt we need to make an effort to seize new opportunities and live our lives to the fullest.