IN FOCUS: Overcrowded south, undeveloped north – Bali seeks new airport, highways and rail lines despite roadblocks

From a new airport that is planned to be built on an artificial island to an extended rail network, how is North Bali planning to make it easier for tourists to get to it?

A tourist relaxes on a paddleboard in Bali's Buleleng Regency. The sea behind her might soon be reclaimed to make way for a new international airport. (Photo: CNA/Wisnu Agung Prasetyo)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

BALI: For decades, the northern coast of Bali has remained a world apart from the island’s bustling south.

While those who flock to the beaches of Kuta and Canggu are drawn to their hip restaurants, bars and nightclubs, here in the north, visitors come to unwind, enjoy unspoiled beaches, trek hilly forests and stroll through villages where ancient traditions still thrive.

But all of that is about to change.

Indonesia has commissioned the construction of a new international airport in North Bali’s Buleleng Regency, an ambitious project that will reclaim 900 hectares of the Bali Sea to form an artificial island.

Designed in the shape of a giant turtle, the airport will feature two runways – one of which can accommodate the world’s biggest commercial plane, the Airbus A380 – as well as a jetty for seaplanes.

In front of it, shopping malls, convention halls and hotels will be built inside a newly developed metropolis that is projected to be the same size as the current biggest city in North Bali - Singaraja. There is also a plan to turn Buleleng into a film production hub which will be nicknamed “Baliwood”.

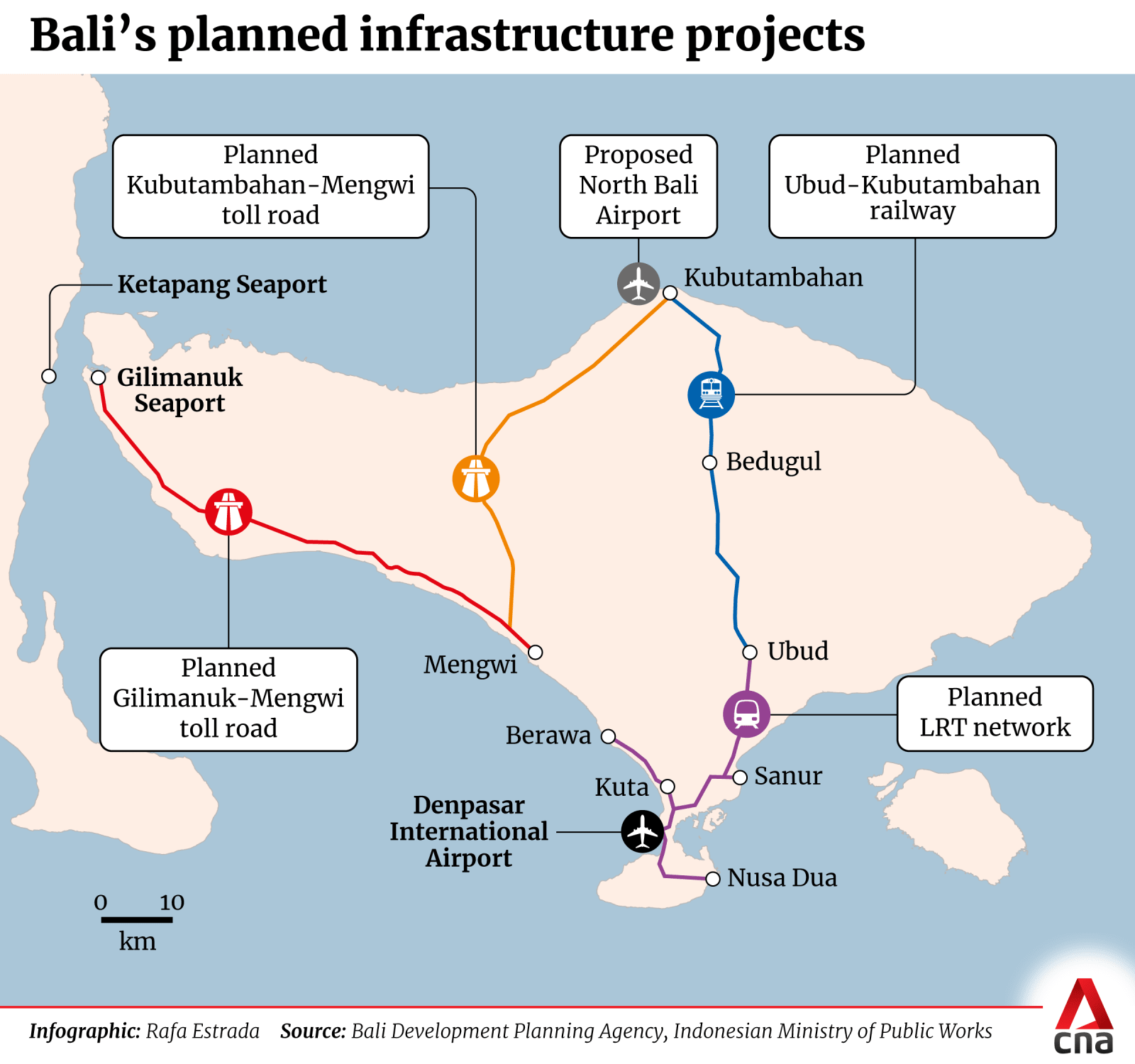

Just a stone’s throw away, a new 60km toll road connecting the quiet North Bali town of Kubutambahan and Mengwi, in the outskirts of Bali’s capital Denpasar - as well as a 100km rail network connecting Kubutambahan with the current Ngurah Rai Airport - will be constructed.

The toll road and rail line will cut through densely forested hills and mountains rich in biodiversity.

There are also plans to revamp ports that dot Bali’s north coast - which today can only accommodate traditional wooden fishing boats - into ones capable of welcoming speedboats, yachts and cruise ships.

Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto has thrown his weight behind these grand plans.

"I am committed to building a North Bali International Airport. We will turn Bali into the new Singapore, the new Hong Kong with the (new airport) area as its epicentre,” the president said on Nov 3, as quoted by Kompas news portal.

For some, it is a welcomed change.

Of the 10 million domestic and 6.3 million international tourists who visited Bali last year, only a fraction - around 600,000 of them - came to Buleleng.

The low percentage is one of the reasons why Buleleng has the highest rate of unemployment and poverty in the tourism-dependent island measuring 5,780 sq km, or eight times the size of Singapore. Buleleng is also Bali’s most populous regency where 826,000 of the island’s 4.3 million population reside.

“We have no youths left in our village, because everyone is looking for work in the south or overseas,” said Made Sudirsa, chief of a village that is around a 15-minute drive from where the proposed airport is set to be built.

“We hope these projects will boost our economy and create jobs.”

But not everyone in Buleleng shares Sudirsa’s enthusiasm, especially towards the presence of an airport. There are those who fear that these projects will lead to the displacement of thousands of residents as well as widespread environmental damage.

“We have seen the impact an airport had on South Bali: Crimes, unruly tourists and the disappearance of villages, rice fields and forests,” said Ketut Artawan, a resident of Kubutambahan.

“We don’t want these things to happen in Buleleng.”

Meanwhile, people in the southern part of Bali are equally split about these planned projects in the north.

“It is important for us in the south to also think about our brothers in the north. They also need tourists and investors to come to their area,” said Anak Agung Ngurah Sukarsana, a Balinese nobleman from the southern regency of Gianyar.

“Meanwhile in the south, we are seeing tourists getting stuck in traffic and missing their flights and people unable to find a hotel room and having to sleep rough. This is bad for Bali’s image. We cannot allow development to only happen in the south.”

But tour agency owner Putu Yoga, who is based in Denpasar, felt differently.

“There are tourists who want to stay away from the hustle and bustle and look for serenity. Some want to go off the beaten path and travel where no other tourists go. Some look for an authentic Balinese experience and don’t want to stay in modern hotels or go to modern restaurants,” he said.

“If North Bali ends up looking just like the south, these people will not come to Bali and go elsewhere.”

Meanwhile, experts are casting doubt on the airport’s feasibility and projected profitability, worrying that it will become just another addition to Indonesia’s long list of underutilised airports such as Kertajati in Majalengka, West Java and Dhoho in Kediri, East Java.

Both of these airports only serve a handful of flights each day.

As for the other infrastructure projects, the major hurdle is money, particularly after Jakarta introduced a raft of budget cuts to various government spending and put a break on major construction projects.

DOES BALI REALLY NEED ANOTHER AIRPORT?

The Ngurah Rai Airport first started as a 700m airstrip built by the Dutch colonial government in 1930 at a sleepy fishing village some 13km away from Bali’s capital, Denpasar.

Over time, nearby beaches like Kuta and Jimbaran morphed into tourism hotspots attracting visitors from around the world. Since then, development has extended further into areas within a 15km to 30km radius of the airport, turning rice fields and lush forests into hotels, villas, amusement parks and restaurants.

As a result, the beaches of southern Bali are overcrowded with tourists and in some areas accessible only via beachfront hotels and shopping malls.

Meanwhile, traffic congestion has become a common sight in southern Bali. On Dec 30, 2023, the gridlock got so bad, many travellers heading to Ngurah Rai Airport were forced to abandon their vehicles and walk for kilometres - with their luggage in tow - to the airport.

But these developments are mostly concentrated on just four regencies in South Bali: Denpasar, Badung, Gianyar and Tabanan and appear to become sparser the further away they are from Bali’s sole international gateway.

And no area in Bali is further from the airport than Buleleng. A car ride between the two can take three to four hours on roads which wind up and down Bali’s hilly interior.

“There has been tremendous development in South Bali. Sadly, this creates issues like traffic congestion, land repurposing, rubbish and so on. But at the same time, we have underdeveloped regions which receive very little tourists,” Bali tourism agency chief Tjok Bagus Pemayun told CNA.

“We have to do something about this so (that the) development can be more equal. We want to encourage tourists to come to the north. One way to do that is to build a second airport in Buleleng.”

Meanwhile, the existing airport is struggling to keep up with demand.

With just one runway, the Ngurah Rai Airport is almost running at its maximum capacity of 24 million passengers per year. In 2024, the airport welcomed 23.6 million travellers, according to operator Angkasa Pura I.

During the holiday seasons like Christmas and New Year, the airport can have around 400 plane take-offs and landings a day.

The airport’s apron - which is the area where aircraft are parked, loaded, unloaded, refuelled, and boarded - has the capacity to hold only 62 planes at a time.

This has, at times, presented a challenge for the airport operator. During the 2022 Group of 20 (G20) summit, Ngurah Rai Airport had to limit the number of regular flights and ban commercial planes from parking overnight in order to make space for arriving world leaders and dignitaries.

There are plans to upgrade its terminals and increase the capacity to 32 million by the end of this year but Angkasa Pura I predicted that this new limit will be reached by 2031.

Sitting on a 269-hectare piece of land at the narrowest point of the hammer-shaped island with the sea on both sides, Ngurah Rai Airport has no room to expand.

“Bali needs another airport. Based on various studies conducted by the national government, the best location for it is North Bali,” Pemayun - the tourism agency chief - said.

WHAT’S THE PLAN?

The idea to build an airport in North Bali has been around for years, promised by various politicians vying for public office to woo voters in Buleleng, where a fifth of the island’s population resides.

“But nothing ever materialised and the main issue is money,” Chappy Hakim, a retired air force general turned aviation analyst, told CNA.

As early as 2018, the Indonesian government has said that Bali’s new airport will not be financed using taxpayer’s money but instead rely on a public-private partnership scheme.

There are currently two airports built with such a scheme: Dhoho Airport in Kediri, East Java, financed by Indonesian tobacco giant Gudang Garam, and the Singkawang Airport in West Kalimantan which was a joint venture involving four of the country’s richest men. Both became operational last year.

Several companies have expressed interest in building an airport in North Bali but one seems to be ahead of the curve: BIBU Panji Sakti. In November, BIBU inked a deal with Chinese firm ChangYe Construction Group.

BIBU chief executive officer (CEO) Erwanto Adiatmoko Hariwibowo told CNA that the Chinese firm has agreed to foot the US$3 billion needed for the construction of the new airport.

“It is a turnkey project, so (ChangYe) will finance everything and once (the airport) is completed, we will reimburse them,” Erwanto said, adding that several foreign investors have expressed interest in the project.

The airport will feature a 3,600m main runway for long haul aircrafts, a second 1,600m runway for private jets and turboprop planes and a jetty for seaplanes. The terminal itself will be in the shape of a sea turtle, a sacred animal in Balinese Hindu tradition.

“We will build (the airport) at sea. It is more expensive and more difficult. But because Bali has so many places of worship, so many temples, it is difficult to avoid them if we build (the airport) on land,” Erwanto said, adding that because no sacred places will be disturbed, he expects less objection from locals.

The plan is to reclaim part of the Bali Sea some 500m off the coast of Kubutambahan to form a 900 hectare artificial island with the airport sandwiched between two commercial and freight service areas.

Erwanto said the company is just one permit away before BIBU can start reclaiming the sea for the project.

“We hope that by the end of 2027, at least one runway will be operational,” he said, adding that the whole airport is expected to be completed by 2030.

BIBU projected that the new airport will cater to 85,000 flights annually once it is fully operational, adding 10 million visitors to Bali.

“We will create 200,000 new jobs,” Erwanto said, adding that the presence of an airport will attract new developments in North Bali.

“We will build a new city to support the airport. There will be five-star hotels, convention halls, theatres, housing, tourist attractions. There will be, what I say, a global film production hub. (The United States) has Hollywood and we will have Baliwood.”

Erwanto said BIBU will work with other firms to build these facilities. It is not yet known how much this project will cost.

Elba Damhuri, a spokesman for the Transportation Ministry, which BIBU said is responsible for issuing its final permit, said it is still studying the firm’s proposal.

ACCESSIBILITY A CHALLENGE

But experts said BIBU’s projection is too ambitious, questioning whether the airport can meet its own targeted deadline for completion.

Aviation expert Chappy highlighted that it took Japan seven years and US$20 billion to build the 510-hectare Kansai Airport before the floating airport opened in 1994. A second 545-hectare artificial island was constructed in 1999 and opened in 2007.

Similarly, it took Indonesian property developer Agung Sedayu eight years - between 2016 and 2022 - to build a 160-hectare artificial island in North Jakarta, which had a similar underwater topography to Buleleng’s coastal regions.

“With today’s technology the construction could be faster but not as fast as (BIBU) would like,” Chappy said.

And to make matters worse, he added that these reclamation projects are now sinking due to coastal erosion, land subsidence and rising sea levels, forcing operators and developers to spend millions of dollars each year to protect them.

Meanwhile, there are those who are sceptical that an airport in North Bali will deliver the promised economic development.

“Do people want to go to North Bali? The problem is those who do are not that many. If the connectivity is the way it is now, (the new airport) will be quiet,” aviation expert Gerry Soejatman told CNA.

Gerry said without a new toll road, the planned airport in North Bali will suffer the same plight as Kertajati Airport in West Java.

Built with a budget of US$158 million, Kertajati was supposed to replace the ageing Hussein Kartanegara Airport in West Java capital, Bandung, a popular tourist destination about a three-hour drive away. But when Kertajati was inaugurated in 2018, it served only one or two flights every other day.

“The airport was operational before a toll road was built. People preferred to fly to Jakarta and travel by land to Bandung, especially now with the presence of Whoosh,” the expert said, referring to Southeast Asia’s first high speed train which opened in 2023.

Even when a 60km toll road connecting Bandung and Kertajati opened in 2023, the West Java airport was still under-utilised. Today, there are seven flights flying in and out of the airport, four of which are not daily.

But BIBU CEO Erwanto is confident that the new airport will not meet the same fate as Kertajati.

“We realise that the airport needs to be supported by other infrastructures,” he said.

The government is planning to build a 60km toll road from Kubutambahan to Mengwi, around 20km north of Ngurah Rai Airport. There is also a plan to build a 60km railway from Kubutambahan to Ubud, a popular tourism hotspot in the hilly regions of southern Bali made famous by the novel and later movie: Eat, Pray, Love.

Erwanto said his company is interested in financing the toll road and railway, although he admitted that BIBU does not yet have a partner willing to foot the bills.

Experts said it is unlikely that the two projects will see the light of day without private funding.

Prabowo, who won last year’s presidential election on a promise of providing free meals to children and expecting mothers, has recently introduced a series of measures to cut down government spending and programmes.

Public Works Minister Dody Hanggodo said at a parliamentary hearing on Feb 12 that the cost-cutting measures will mean delays on the completion of some ongoing projects and the postponement of those still on the drawing board, including a host of projects in Bali.

Dody, however, welcomed the private sector to finance these projects, adding that Jakarta is willing to provide investors with tax breaks and other incentives.

The impact of these austerity measures can be seen in Bali.

The Ministry of Public Works is supposed to build a 96.8km toll road connecting Mengwi and Gilimanuk Port in the northwestern tip of Bali island. The port is the main gateway for travellers entering Bali from Java via the sea.

But local media reported that aside from the acquisition of several plots of land, there has not been any significant progress in the two years since the project broke ground. The Mengwi-Gilimanuk toll road is reportedly meant to connect to the proposed Mengwi-Kubutambahan toll road.

Meanwhile, Bali’s light rail train (LRT) network also showed no significant progress since it broke ground in September aside from an empty parking lot earmarked to be its main interchange station. When CNA visited the site in late January, it was desolate with no workers or heavy machinery in sight.

The 33km Bali LRT network, designed to combat southern Bali's worsening traffic, is supposed to connect with the proposed Ubud-Kubutambahan rail line.

MASSIVE IMPACTS AND POTENTIAL ROADBLOCKS AHEAD

It takes years to build toll roads, railways and LRT networks.

The Bandung-Kertajati toll road, for example, started work in 2011 before it opened 12 years later. Meanwhile the 43km Greater Jakarta LRT network had been in development since 2015 before the first two lines were operational in 2023.

According to the Ministry of Public Works’s projection, the Gilimanuk-Mengwi toll road will not be finished before 2028. Mengwi is about 75 minutes from where the current Ngurah Rai Airport is located. The portion which connects Mengwi to the airport is still being formulated.

Meanwhile, the Bali LRT is expected to open its first two lines by 2031. The lines will connect the planned airport with Cemagi beach, just north of Denpasar and Nusa Dua in the south. It is not clear when the line leading to Ubud will be built.

“Forcing an airport to be built now does not make much business sense,” said aviation expert Gerry.

The only way the new airport can attract passengers is to price its landing, parking and passenger handling fees lower than Ngurah Rai.

“Maybe that will be enough to convince low-cost carriers to open up a flight there but not full-service ones because all the tourist destinations people want to go to are in South Bali,” he added.

But having the new airport catering exclusively to low-cost carriers does not bode well with some in Buleleng.

“The type of people who travel using low-cost carriers are usually those who are young and want to have fun hopping nightclubs. We don’t have that here and I don’t think people want that here,” chief of Buleleng Tourism Agency, Dody Sukma Askara, told CNA.

“Instead, we want people who are willing to spend money to enjoy the natural beauty, serenity and quiet life Buleleng has to offer.”

Diving centre provider Komang Astika echoed the sentiment. “An airport will create noise which might scare off the dolphins and other wildlife which Buleleng is famous for,” he told CNA.

Buleleng resident Artawan said news that an airport will be built is enough to drive property prices up in the regency.

“I have had people from Denpasar, Surabaya, Jakarta come up to me looking to buy land in Buleleng. Unfortunately, there are plenty of locals who are willing to sell because they need the money,” he said.

Artawan is also sceptical that an airport will create better job opportunities for the locals.

“Of the 200,000 jobs they promised to create, I think most of them will be low-skilled and low-paying positions while the high-paying jobs will go to newcomers from other areas,” he said.

But Buleleng resident Kertut Arcana Dangi hopes that the promise of job opportunities in Buleleng will get locals to stay.

“I have had members of my extended family leaving Buleleng because there is simply no work for them here. There are just not enough tourists,” he told CNA.

BRACING FOR AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE

Tourism agency chief Askara acknowledged that some tourists who come to Buleleng find the journey lengthy and tiresome. But he argued that most of them are more than happy with a toll road or a railway line which will cut travel time significantly.

As Buleleng waits for the toll road and railway line to be built, the regency is thinking of other ways to make the journey to Buleleng more bearable.

One way is to deepen the sea and revamp its ports so they can cater to speedboats, yachts and cruise-liners travelling from either Java or Lombok.

“We are working together with the governments of East Java and (Bali’s) Karangasem (regency on the eastern part of the island) because we noticed a trend of travellers first arriving in East Java and then travelling to Buleleng and Karangasem before returning home from either Denpasar or Lombok,” Askara said.

The only downside is that the ferries connecting East Java’s Ketapang and Bali’s Gilimanuk seaports are old and not well-maintained. The long queues of ships waiting to dock at these small ports is also an issue, particularly during the holidays.

“Why not establish a speedboat route connecting Ketapang, Buleleng, Karangasem and (Denpasar’s) Tanjung Benoa. That way tourists can travel faster and more comfortably,” he said, adding that there is no specific timeline on when these projects will commence.

Meanwhile, the Buleleng government is bracing for the prospect of an airport built in their backyard.

“The Buleleng government welcomes (the new airport) because it is meant to develop people’s economy and income,” Askara said. “But we must ensure that we mitigate the negative impacts of this development.”

The regency is deliberating on a stricter zoning law, stipulating where and what type of new businesses are allowed to be built in Buleleng.

“We have seen how a lack of regulation created crippling traffic, over-tourism and unsustainable tourism practices in the south,” he said.

“We will do what we can to prevent that from happening to Buleleng.”