IN FOCUS: Is it too late to defuse the ‘ticking time bomb’ of Malaysia’s fast-ageing population?

Caregivers lacking respite and support, seniors who need more age-friendly infrastructure and financial security – will Malaysia’s upcoming white paper to tackle an ageing nation rise to the challenges?

Elderly residents at an old folks' home in Subang Jaya, Selangor. (Photo: CNA/Fadza Ishak)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

KUALA LUMPUR: After Siti Zaharah Mat’s father died in 2015, she and her six siblings took turns caring for their mother at their own homes for a few years.

But her mother preferred to live with Siti Zaharah, who is single.

“Most parents prefer to stay with their own children, compared to their daughter-in-law or son-in-law,” Siti Zaharah explained. “Furthermore, I’m not yet married and I don’t have any kids.”

So, just before the pandemic hit in 2020, their mum, now 86, began living with Siti Zaharah in Semenyih, and the 40-year-old lawyer took on the sole responsibility of caring for her.

She cooks and cleans for her mother and keeps a close eye on her, making sure the older woman takes her medication for diabetes, high blood pressure and heart issues.

Her mother is able to move around independently but is a fall risk as she has osteoporosis and a curved spine. Various health issues have also confined her to the bed on several occasions.

Siti Zaharah credits her “very understanding and supportive” boss, who has given her the flexibility to start work later and end earlier to cope with caregiving responsibilities.

For urgent tasks, she is allowed to work from home instead of making the 45-minute drive to her office in Kuala Lumpur.

Still, Siti Zaharah feels compelled to sell insurance on the side to help cover her expenses, which include a car and housing loan as well as medical fees for her mum.

She admits that caring for her mother, alongside working two jobs, has taken a toll on her social life.

“Being a single person, my friends always ask me to travel together, have a staycation, or go healing somewhere … I cannot simply say yes,” she said.

Siti Zaharah has considered day care at a centre for her mother or even moving together with her into a longer-term facility, which she said would “make my life easier”.

But she reckons the older woman, who grew up in a kampung, might have more traditional views of filial piety, and she must first think of the “best approach” to broach such arrangements.

“I have to be very careful with that, because my mum is a super sensitive person,” she said.

Caregivers’ needs, retirement adequacy and services catering to seniors with different abilities are issues that have come to the fore as Malaysia’s government gets ready to table what it calls a White Paper on Ageing Nation Agenda.

The agenda will be a prime focus of the 13th Malaysia Plan, a roadmap to tackle global shifts and domestic challenges, and the white paper could be tabled at the next parliamentary sitting in June or July. The 13th Malaysia Plan will also be debated at the sitting.

Malaysia is already an ageing society, with 8.1 per cent of its population aged 65 and above in 2024, according to the United Nations (UN) Development Programme.

This proportion is set to rise to 14.5 per cent – pushing Malaysia into aged status – by 2040, which is sooner than expected. The government’s previous forecast was 2044.

The UN defines an ageing society as one where more than 7 per cent of the population is aged 65 and above. When this proportion crosses the 14 per cent and 20 per cent mark, the society becomes aged and super-aged, respectively.

Malaysia is ageing rapidly due to longer life expectancy and a fast declining total fertility rate.

In February, Women, Family, and Community Development Minister Nancy Shukri told parliament that Malaysia's total fertility rate declined from 2.2 in 2012 to 1.7 in 2023. The replacement rate needed to maintain the population from one generation to the next is 2.1.

Economy Minister Rafizi Ramli first announced last August that the government was planning to table an ageing nation white paper this year, saying officials had come up with a framework and action plans to tackle the trend.

While few details on the white paper have been released, Rafizi reportedly said it would address “weaknesses” in social protection, particularly for pensioners.

Rafizi said last November that the white paper would also look at areas like insurance, pensions, as well as legal aspects to develop the country’s care industry.

In response to CNA’s question at a 13th Malaysia Plan briefing in February, an economy ministry official said the white paper will cover aspects like the labour economy, education, health and long-term care.

“COULD HAVE PREPARED EARLIER”

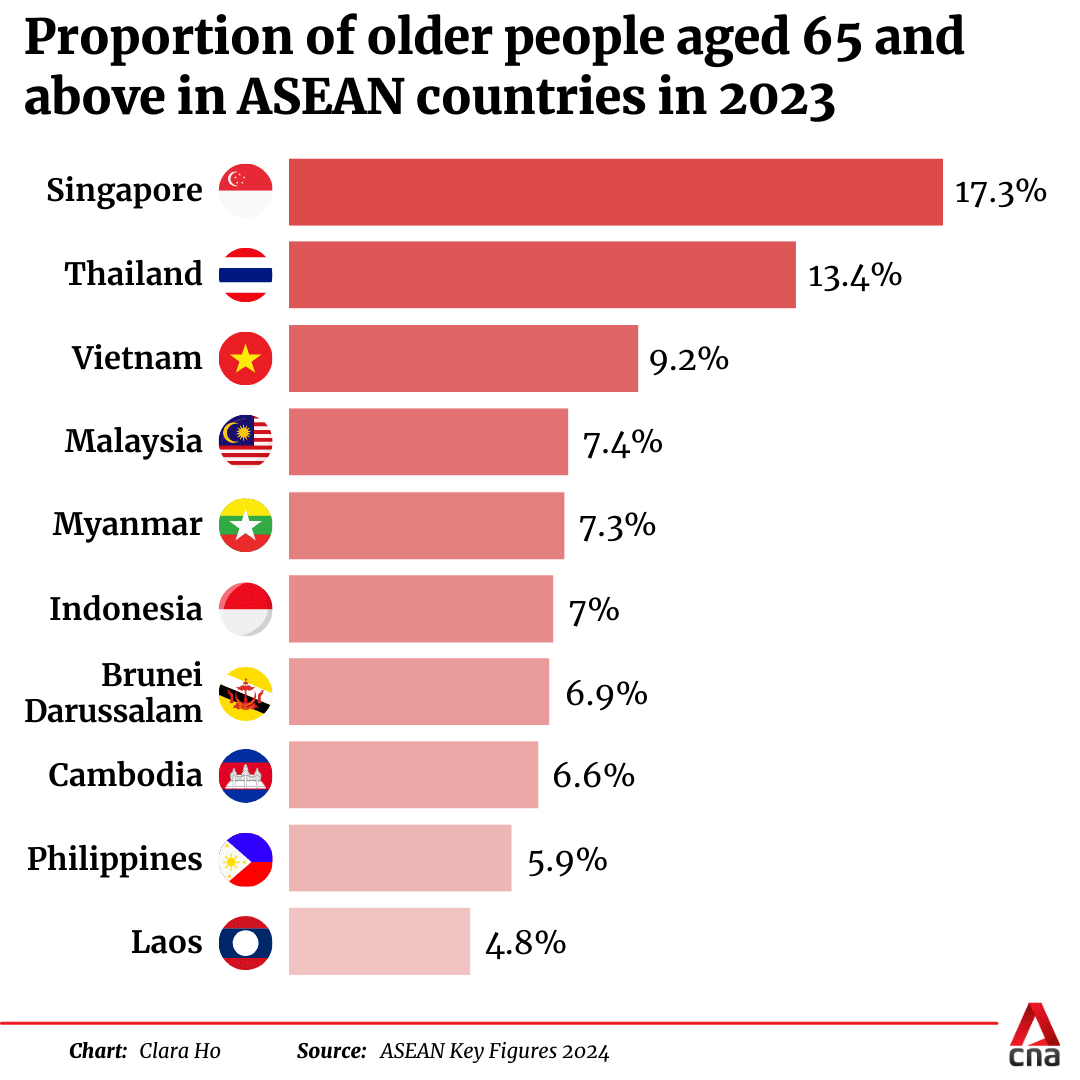

Within Southeast Asia, Malaysia had the fourth-largest share (7.4 per cent) of people aged above 65 in 2023, according to figures from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) secretariat.

Vietnam (9.2 per cent), Thailand (13.4 per cent) and Singapore (17.3 per cent) have greyer populations.

Like some of its Southeast Asian neighbours, Malaysia is reaching aged status faster than expected. Some observers question if the government is acting too late.

Lee Min Hui, a gender consultant at the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), said Malaysia is already seeing the effects of limited support for older persons.

“With women dropping out of the labour force for care work and older persons increasingly facing issues around care dependency and affording care, it would have been ideal if these preparations could have been made earlier,” she said.

“This is not least because it takes time to build the kind of infrastructure, framework, support and mindset changes required to ensure a truly holistic response to ageing.”

Social Wellbeing Research Centre director Norma Mansor too believes the white paper could have been tabled “sooner”.

But “it is not too late”, she said, noting Malaysia’s median age of 31 compared to Singapore’s median age of 43.

Singapore set up a ministerial committee on ageing in 2007 when 8.5 per cent of its residents were aged 65 and above.

In 2015, the committee launched the first Action Plan for Successful Ageing comprising over 70 initiatives such as supporting seniors to pick up new skills, upgrading estates to be more senior-friendly, and expanding aged care facilities.

It launched a refreshed action plan in 2023.

What are Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam doing to tackle ageing societies?

Singapore has the largest share of seniors in ASEAN, with one in four people estimated to be aged 65 and above by 2030.

The government refreshed its Action Plan for Successful Ageing in November 2023 to include efforts to keep older people employed for longer and connected with their loved ones.

The action plan’s Live Well, Age Well programme, which targets people aged 50 and above, offers activities such as group exercise sessions and educational sessions on mental well-being.

Older adults can also enrol in the Healthier SG initiative, which aims to more strongly emphasise preventive care by pairing residents with family doctors to help them better manage their health.

In 2021, Singapore passed a Bill to allow the retirement age and re-employment age to be raised by three years to 65 and 70 respectively by 2030.

To boost retirement adequacy for seniors, Central Provident Fund contribution rates for workers aged above 55 to 70 would also be raised over the next decade.

In Thailand, more than 20 per cent of the population is aged 60 or above, and the country is set to become a super-aged society – where more than 20 per cent of people are aged 65 and above – within the next decade.

Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra has pledged to improve Thailand’s universal healthcare system to meet these demographic challenges. Last month, the government handed out about 30 billion baht (US$890 million) to its senior citizens.

Bloomberg reported more than three million senior citizens were given 10,000 baht each, with the stimulus expected to boost the country’s economy. Paetongtarn said the programme will continue, without giving further details.

The Thai government has also outlined three main strategies to boost its declining fertility rate: Promote childbearing and child-rearing, introduce flexible working hours for women with young children, and improve access to reproductive health services.

Over in Vietnam, more than 16 per cent of its population is considered elderly, with this proportion set to increase to almost 20 per cent by 2036, a Viet Nam News report published last October said.

The country emphasises employment for its elderly, noting their valuable skills and experience as well as potential economic contributions.

In December 2021, the government approved a National Action Programme for the Elderly, which aims to ensure at least 70 per cent of the elderly who have the need and ability to work are employed by 2030.

Under the programme, at least 30,000 elderly people will also be supported to set up new ventures, or receive vocational training, the report said.

In Malaysia, “we still have that window for us to plan and be able to reap the benefits of the silver economy”, said Norma. “But if we don’t do it now, then we’ll be too late.”

The white paper should address the development of Malaysia’s care economy, which includes affordable care for elderly people of various abilities as well as social protection for informal caregivers at home, experts said.

The white paper should also cover aspects like financial security, age-friendly infrastructure, and healthy ageing, they added.

CARE ECONOMY BENEFITS ALL OF SOCIETY

Building the care economy is crucial, said Lee, referring to productive work – either paid or unpaid – that supports caregiving in all its forms, primarily for dependent groups including the elderly.

A fast-ageing population could expose the country’s lack of healthcare and social care facilities, as well as exacerbate inequality, experts said.

Reports of elderly persons being abandoned in hospitals and care centres are a possible sign of gaps in caregiving provisions, they add.

Hospital Kuala Lumpur saw a 50 per cent rise in patients being abandoned over three years, with 358 cases in 2023, up from 239 cases in 2020, local media reported. About half of these patients were above the age of 60.

Shahrul Bahyah Kamaruzzaman, president of the Malaysia Healthy Ageing Society, a non-profit organisation that educates stakeholders on healthy ageing issues, told CNA that elderly abandonment could be due to a range of socioeconomic and health issues.

“It’s symptomatic of caregiver burden and stress, inadequate or unequal access to care, rising medical costs and unhealthy ageing,” she said.

Lee said the caregivers in the abandonment cases probably just needed respite care, but ended up putting more pressure on the already strained public healthcare system.

She called on the government to explore integrated care systems that can make the country’s social care infrastructure “a worthy complement to our healthcare system”.

According to an editorial published last August in the Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences, integrated care systems are those that coordinate healthcare services across various providers and settings.

These include hospitals, primary care clinics, community health centres and long-term care facilities, said the editorial on healthy ageing in Malaysia by 2030, which was written by three members of the National Council of Professors.

“This ensures seamless transitions between different levels of care and improves continuity of care for older adults,” the professors wrote.

Lee stressed that a good baseline of care services will not only benefit the elderly, but also working-age families, primarily women, who take up the bulk of care work.

These individuals often have to reduce their work hours or drop out of the labour force completely to care for a dependent, she said. This creates “huge” knock-on effects on productivity and economic growth.

Norma from the Social Wellbeing Research Centre said there are around 3.2 million Malaysians, including women, who are not working due to caregiving duties.

If these individuals entered the workforce, they could contribute 4.9 percentage points of gross domestic product (GDP) growth, she said. For comparison, Malaysia’s economy grew 5.1 per cent in 2024.

Lee said informal caregivers can be supported through social assistance measures such as cash transfers, cash-for-care benefits, family allowances or pension credits.

“Using transfers to offset that loss of income could potentially prevent the further deprivation of low-income caregivers, who often arrive at old age with very little savings and social protection,” she added.

From interviews with caregivers, the weight of their responsibilities was clear.

In Petaling Jaya, a city neighbouring Kuala Lumpur with a sizeable elderly population, CNA approached a woman sheltering her frail mother with an umbrella as they trudged towards a market.

The woman, who is in her 40s and declined to be named, said she had to switch to a job with more flexible working hours to better care for her mother and bedridden father.

Her parents, both in their 70s, prefer to live at home instead of a residential care facility.

“Luckily, I don’t have children,” she said.

The woman said she currently faces challenges applying for disability aid for her father, as the process requires him to be transported to and from a government hospital.

She hopes the government can provide more financial assistance to caregivers of the elderly, and make the process of applying for social aid more seamless.

“Malaysia’s ageing population is only going to get worse pretty soon. How are we going to tackle that? I do not know,” she said.

Malaysia currently offers personal tax relief of up to RM8,000 (US$1,800) for parental care expenses, including fees for daycare centres or nursing homes. However, the government does not subsidise fees for private facilities.

Siti Zaharah hopes the government can help defray the costs of caring for elderly parents at home, including for items like medicine, healthcare trips and mobility devices.

“Maybe they can give more tax incentives, but for me personally, I would prefer cash,” she said.

“Our salary is just enough to cover (our own expenses) and, living in KL, the cost of living is very high. So I think if the government can give a cash programme, that would be very helpful.”

INSURANCE, PENSION SCHEME FOR BETTER RETIREMENT ADEQUACY?

For 40 years, Mohd Yusoff Ahmad, 63, and his wife have run a Malay food stall at a Petaling Jaya market.

Although some of their peers have retired, the couple have chosen to keep working as a way to keep active and earn side income.

Many of the other seniors CNA spoke to at the market also expressed a desire to work for as long as they could.

“If you don’t have money, that’s when the challenges come (as an elderly person),” Mohd Yusoff said.

“If possible, we do not want to be a burden (on public resources). As long as we can be independent, we will. We cannot hope for state aid; there are others who need it more,” he said.

Analysts, however, believe government intervention will be needed to ensure Malaysians have enough for their retirement.

Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, when unveiling this year’s budget last October, announced that allowances for needy senior citizens would go up from RM500 to RM600 per month.

This is part of an RM1 billion allocation that will also go towards building more government nursing homes and senior citizen activity centres.

For retirement needs, UNFPA’s Lee feels that Malaysia’s employment-linked social protection scheme – the Employees Provident Fund (EPF) – is insufficient as lifespans increase.

As of last October, only 36 per cent of active formal EPF members had met minimum savings of RM240,000 by age 55 to cover essential retirement needs, she noted.

The government should consider some form of long-term care insurance or social pension, Lee said, referring to a government-funded programme that aims to provide a minimum standard of living in old age for everyone regardless of contributions.

“The government really has to play a role, because at this point, we are already an ageing nation. We're going to be in what people have said is a ticking time bomb (situation), and we are already seeing the effects of it currently,” she added.

The poverty rate among older persons in Malaysia is around 42 per cent, more than double the national poverty rate of 17 per cent, noted Norma from the Social Wellbeing Research Centre.

“Older people becoming poor is one phenomenon (we will see) going forward in Malaysia,” she said.

To tackle this, the government could fund a social pension scheme by introducing a broad-based consumption tax rate of as low as 2 per cent, she said.

“The reform that we hope to see happening is what we describe as a multi-tiered income for old age,” she added.

“That at the very lowest, every Malaysian should receive some kind of basic social pension, and that should be tax-funded.”

Last June, the chief executive officer of a civil service retirement fund reportedly stressed a need to revisit pension plans and social security systems to ensure retirees can support themselves through a longer retirement period.

Retirement Fund Incorporated CEO Nik Amlizan Mohamed was also quoted as saying Malaysia should re-evaluate the minimum retirement age of 60 in light of rising life expectancy.

Federal Territories Minister Zaliha Mustafa responded that the government had no plans to raise the retirement age for civil servants.

Under the current system, healthy and independent seniors can already continue working beyond the statutory retirement age, said Calvin Cheng, an economics fellow at Malaysia’s Institute of Strategic and International Studies think tank.

The retirement age only serves as a social yardstick for when people should transition into retirement, and to reduce job protections and required benefits for people beyond the retirement age, he explained.

Cheng told CNA that the way forward seems to be allowing people to “self-select into retirement” at a time that best maximises their personal well-being.

“This may mean for now, maintaining the current statutory retirement age (of 55) but providing incentives for those who wish to keep working,” he said.

In the medium term, as life expectancy and quality-adjusted working years rise, the statutory retirement age could be gradually increased to protect workers for longer, he suggested.

“In tandem, the minimum EPF withdrawal age could also be raised progressively – though kept below the statutory retirement threshold – and in the longer term, eventually transitioning to an annuity-based system for private pensioners,” he added.

“But this needs to be approached with a large degree of political and social sensitivity, and also be accompanied by other policies: Age-friendly workplaces, greater social protection coverage, and tailored senior reskilling opportunities.”

The government should also educate the public on retirement adequacy earlier, said Shahrul Bahyah of the Malaysia Healthy Ageing Society.

“I think that needs to be taught in schools and colleges so that younger people know what they need to do in order to respond to the impact of population ageing,” she said.

Shahrul Bahyah opined that social care could also be made more affordable through better regulation of services like senior homes, and enforced with feedback from the community.

IMPROVE COMMUNITY-BASED SERVICES, EXPERTS SAY

With many seniors CNA spoke to preferring to live at home instead of care facilities, experts say community-based services must improve to support successful ageing-in-place.

“This involves establishing community health centres, daycare centres and homecare services to provide older adults with access to healthcare, social support and recreational activities within their communities,” said the editorial in the Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences.

What do senior care facilities hope to see?

Malaysia has 393 registered elder care centres and 26 nursing homes, with an additional 700 to more than 1,000 unregistered facilities, according to a United Nations Development Programme report published last June.

Even with most families preferring to care for their elderly at home, many facilities already face long waiting lists, and the demand will only increase in the coming years, it said.

Phang Sue Ling, a doctor and co-founder of Genesis Life Care, a long-term care service provider in Malaysia, believes the timing of the white paper is “a bit too late”.

She estimated that Malaysia has only about 30,000 care centre beds, while its much smaller neighbour Singapore has already made plans to expand its nursing home bed capacity to 31,000 by 2030.

“We have so much more to catch up on. And with all this bureaucracy, for even private sector people to open up centres to help ease the burden we have, it's not easy for us as well,” Phang told CNA.

Genesis, which provides services like stroke rehabilitation, dementia care and palliative care, operates four centres in Klang, Kajang, Petaling Jaya and Puchong, with the Klang and Petaling Jaya outlets at more than 90 per cent occupancy.

Phang hopes Malaysia’s upcoming ageing nation white paper can streamline licensing requirements for care centres, such as the maximum number of floors permitted.

Nithiyaraja Selvarajan, founder of Sukha Golden Sanctuary, a day centre for seniors in Petaling Jaya, said the single licensing regime should also apply across state governments and city councils.

“You have these little Napoleons, where they impose things which sometimes make it tough for operators to get a licence,” he told CNA, referring to state and local authorities.

Selvarajan estimated that less than 20 per cent of senior living facilities in Malaysia are licensed.

Both Selvarajan and Phang lamented the lack of financial support from the government in operating these private facilities, suggesting tax breaks as one measure they would be grateful for.

“We don't want to charge too high, because you want to provide that service to the community, but at the same time we want to stay afloat,” Selvarajan said.

While Phang acknowledged the government had more pressing expenditure needs, she asked if Genesis could get tax exemptions for every patient it takes in from the Department of Social Welfare and cares for at subsidised rates.

“This, I think, can be a way that we work together with the government to solve our problems,” she added.

Over at the Kenang Budi Welfare Organisation, a traditional old folks’ home in Petaling Jaya, its manager Jason Wong said more volunteers are needed to help out with day-to-day operations.

These homes, usually a bungalow-style basic facility, are often run by non-governmental or religious organisations. They offer free accommodation for seniors in need and rely on public donations as well as a yearly but irregular stipend from the government.

Wong’s facility takes in only government- or hospital-referred seniors who do not have next-of-kin, or relatives willing to care for them. The home, which has since moved to Subang Jaya, can house 19 residents. It now has 17 residents after two recently died.

“In one year, I can have six to seven new residents,” Wong told CNA. “The problem (of demand exceeding supply) will only worsen as Malaysia ages.”

At the other end of the senior home spectrum is the Millennia Village in Seremban, which offers resort-style independent living.

The price for a couple starts at RM6,500 a month including full board and meals.

Millennia Village chairman John Chia said he is getting a lot of interest from foreigners from countries like China, Japan and Singapore who cannot afford to retire in such a high-end facility back home.

He urged the federal government to relax the housing purchase requirement in Malaysia’s retirement visa scheme and allow foreigners to qualify if they choose to lease a unit in such a facility.

As for locals, Chia said a senior couple living in Kuala Lumpur would probably spend more living by themselves than at Millennia Village, based on a rough calculation of rental, utilities, meals and domestic helper fees.

Opting to live in such a communal facility entails a “mindset change” – one that Chia thinks an increasing number of seniors will make.

“With people living longer and being more affluent, and their children not living with them anymore, I think there will be greater attraction (to such facilities),” he said.

Shahrul Bahyah, who is also a professor of geriatric medicine at Universiti Malaya, said the white paper should look at creating more age-friendly infrastructure.

“Ensure that each neighbourhood has a community health hub, with access to regular checkups with a general practitioner, screenings, and healthcare resources if they need to traverse primary, secondary, tertiary healthcare,” she said.

“A lot of the stresses that our ageing community goes through is that they don't know where to go, and if they need to go and get something, they feel that they need to pay.”

Shahrul Bahyah called for more elderly-friendly urban planning and housing, as well as improved accessibility, noting that it remains difficult to go about on foot in the capital Kuala Lumpur.

In Singapore, some public housing is co-located with nursing homes and senior activity centres. The government also offers senior-friendly apartments with care services that can be scaled according to care needs and social activities.

“Unlike how cohesive and integrated things are in Singapore because of governance and leadership, it’s a bit complicated in Malaysia,” Shahrul Bahyah said.

“We have to work with state governments and their different systems … But we hope that via city councils in each state, they have some kind of integration.”

That said, residential care facilities have their place in the landscape.

At the Petaling Jaya outlet of Genesis Life Care, a long-term care facility, a woman who only wanted to be known by her surname Gan watched as her 86-year-old mother underwent physiotherapy after a fall at home.

Gan, a 65-year-old retiree, said her mother is already showing signs of improved mobility after living at the home, which she praised for its modern facilities and knowledgeable staff.

“If possible, no family would want to check their elderly parents into a nursing home, but sometimes we just don’t have the skills,” she said. Transferring an elderly person to and from a bed can be difficult, for instance.

“You can go for physio (in outpatient settings), but every day you have to send and fetch them,” added Gan, noting that some families might not be living near such facilities.

But residential care services do not come cheap, and she urged the government to help ease the costs of such services.

Government-subsidised facilities are always full, she said, while more traditional bungalow-style old folks’ homes could be affordable but rarely come with rehabilitation services or activities.

At Genesis, a package for independent living, which includes accommodation, meals, housekeeping and activities, starts from about RM2,400 a month.

Residents who need doctor consults or physiotherapy could be charged an extra RM60 to RM80 per session, with the most expensive package being RM4,500 for a bedridden resident in a larger unit who needs tube feeding, help with shifting positions to prevent bed sores, and wound care.

HEALTHY AGEING AND BOOSTING ELDERCARE WORKFORCE

The authorities should also help Malaysians stay healthy in old age, experts say.

This involves preventive care and chronic disease management from a younger age, as well as more strategies that encourage healthy living, said Shahrul Bahyah.

“Our economy ministry needs to look at taxes on cigarettes and sugar, among other things, to try and make it a little bit more of a cohesive strategy,” she said.

Malaysians are living longer, although not necessarily in good health.

Based on current trends, an estimated 9.5 years will be spent in poor health due to non-communicable or chronic diseases, according to the government’s health white paper tabled in 2023.

The government also acknowledged it is under-investing in health, stating that as an upper-middle income country, it spent only 4.1 per cent of its GDP on health in both the public and private sectors. This is lower than the average of 7.4 per cent of GDP among other upper-middle income countries.

“Rising burden of disease, an ageing society, changes in technology, increasing demand for pharmaceuticals and consumables, are amongst many factors driving up the demand for greater health investments and expenditure,” the health white paper said.

Malaysia’s healthcare workforce should be equipped with the knowledge and skills to handle the specific needs of older people, Shahrul Bahyah suggested.

Given the demographic shift, the government should also actively promote eldercare as an attractive career option, said Seow Zhi Heng, who started as a physiotherapist at Genesis before being promoted to manage its Petaling Jaya outlet.

Eldercare roles are in demand, and Seow encouraged younger Malaysians to explore opportunities in the sector as the skills they learn could prove useful in future.

“We all have our parents and grandparents, and they are slowly ageing by the day. So, we have to get to know what we will be facing next time,” the 28-year-old said.

“Your parents might have a fall, stroke or heart attack. Working in this industry will give you the experience of knowing what to do if something happens.”

Gan, the retiree whose mother is a Genesis resident, said she hopes her children will care for her in the future, but acknowledged that realities have changed.

“We want to rely on our children to care for us, but they all have careers,” she said.

“It’s better to save enough money, so at least I can go to this type of facility if I really need to.”