Commentary: The human advantage in the age of AI

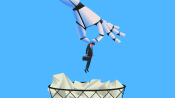

While AI can perform many tasks better than people can, there is no replacing human beings in key roles such as building trust and influencing others, says SUSS’ Terence Ho.

File photo of business people at a conference. The nature of work could change significantly with AI, but human beings have the inherent advantage in understanding and influencing decision makers.

(Photo: iStock/Edwin Tan

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Last month, artificial intelligence (AI) chalked up yet another win as an advanced version of Google’s Gemini AI model correctly solved five out of six questions in the International Mathematics Olympiad - a gold medal result in the world’s premier mathematics contest for pre-university students. This was an improvement over its silver medal showing in 2024, underscoring just how quickly AI is improving.

Humankind was nonetheless offered a rare reprieve in the contest between man and machine as Polish programmer Przemyslaw “Psycho” Debiak beat an OpenAI model in a 10-hour marathon coding contest in Tokyo.

Even so, it is only a matter of time before such contests swing in AI’s favour, as technology advances relentlessly. This poses the question: Are there any domains where human beings will always have an enduring advantage over AI, and where human relevance is beyond doubt?

Related to this issue is how schools and tertiary institutions ought to prepare the next generation for the age of AI.

WINNING FRIENDS AND INFLUENCING PEOPLE

As the debate over the impact of generative AI on jobs rages on, certain things have become clear.

Large-scale job loss is unlikely, but the nature of work could change significantly. Skills like graphic design, professional writing or coding that were once relatively scarce may become less so as AI equips laypersons with the tools to become effective designers, writers or “vibe” coders.

At the same time, new jobs will be created, just as the industrial age, the computer era and the advent of the internet introduced entire new classes of jobs that did not previously exist. The question is whether there will be more good jobs or grunt jobs for human beings – whether AI will take over the choicest tasks, or whether it will free people from drudgery and empower them to pursue work with greater meaning.

One reason to be hopeful is the inherent advantage human beings have in understanding and influencing decision makers. It is unlikely that consumers and business owners will ever fully devolve to AI decisions on purchases, investments and hiring. This is because such decisions are deeply personal, reflecting individual preferences, comfort levels and trust.

As long as there is a need to convince decision makers of a course of action, human beings have a unique advantage. They are able to read a person’s tone and body language, to judge his or her mood, and bring to bear knowledge of the person’s preferences and proclivities in a way a machine cannot.

Generative AI excels in text and logic as it is trained on vast amounts of recorded material. But much information about a person isn’t codified, even if he or she is a prominent figure. This means that someone who actually knows the decision maker, or who has at least interacted with the person before, will be at a considerable advantage over AI in knowing how to make an effective presentation or sales pitch.

The adage “Whom you know is more important than what you know” still holds true in the age of AI. Networking and trust-building are uniquely human endeavours. AI can help draft a speech or spruce up a presentation, but the human insight into others remains critical.

Leadership, too, is an inherently human exercise. Human leaders will still be relied on to organise people and lead teams, as success hinges on communication and trust, negotiation and compromise, beyond mere algorithms.

THE HUMAN FACTOR IN STORIES AND SPORTS

Another innate human advantage is the power of connection through storytelling. Human communicators will always have an edge over AI in being able to tell authentic stories from personal experience.

This is evident in books and movies. Fiction draws readers because it recreates human drama in imagined settings, but there is a unique place for the memoir, or narratives based on actual people and events.

Consider The Salt Path, a 2018 bestselling memoir recently turned into a movie. It recounts the story of the author and her husband, who set out on a long walk after losing their home and learning that one of them had a terminal illness. Their journey inspired readers with its story of human triumph over despair. A subsequent report by The Observer newspaper disputed key events underpinning this narrative. Regardless of the merit of these claims, the doubt cast on what is billed as a true story has had significant repercussions for the book’s marketability.

The world of sports provides another illustration. Much of the allure of sports lies in human drama – in human rivalry, the rise and fall of stars, in battling against the odds, and in the split-second decisions that alter the course of a match. Even in chess, where computer engines have long surpassed the best human players, livestreamed blitz and rapid tournaments are gaining online viewership, with human fallibility itself part of the draw.

Just as handcrafted products command a premium in the era of mass production, human involvement in content creation – whether in books, film or sport – will be highly valued in the age of AI.

SKILLS AND CONTENT MASTERY WILL REMAIN CRITICAL

Much of the conversation on generative AI and education is about whether it is still worthwhile to learn skills and content where AI can clearly outperform human beings. The answer has to be a yes, because that is the only way human beings can understand, interpret and use AI output effectively.

In the extreme, someone without basic literacy would have no way of making sense of a large language model’s (LLM) output; a primary schooler’s understanding of a topic such as magnetism would be very different from a physics graduate’s understanding, even if both were to interrogate the same LLM.

In the same way, those with a deep appreciation of writing and style can use AI-generated text more effectively than someone who does not grasp the rudiments of composition. The same applies to other creative domains such as art, design and music. Experts will still be needed to validate and where necessary, adjust AI-generated output to achieve desired outcomes.

AI can do much of the heavy lifting in software programming, but when something goes wrong with the code, a software engineer’s deep knowledge may be required for troubleshooting.

At the cutting edge of research in any field, it will be subject matter experts leveraging AI who have the best chance of pushing out the frontiers of knowledge, certainly when compared with non-experts with access to the same AI tools.

This is why some worry that if AI takes over entry-level jobs, many young professionals will never acquire the experience and expertise necessary to add value to AI. It therefore behoves employers to give opportunities to young workers, and for workforce entrants to leverage AI and human skills to contribute to their organisations from the get-go.

Recognising the unique ability of human beings should be an encouragement to individuals and employers to continue investing in human skills and competencies, as well as subject matter expertise, so that AI will augment rather than undermine human capability.

Terence Ho is Associate Professor (Practice) at the Institute for Adult Learning, Singapore University of Social Sciences. He is the author of Future-Ready Governance: Perspectives on Singapore and the World (2024).