commentary Commentary

Commentary: Government matchmaking programmes need a rethink to get singles to mingle

More than 30 years since the Social Development Unit was formed, the Government’s matchmaking programmes might be in need of a review, says one observer.

A couple on a date. (Photo: Unsplash/rawpixel)

SINGAPORE: Last month, the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) released Singapore’s annual Population in Brief report.

The report showed that the proportion of singles in most age groups had gone up, with the biggest increase among Singaporean women aged 25 to 29.

Many have questioned whether the government’s social development programmes have been effective as a result. Some have asked whether they were just a waste of time and money, and should be discontinued.

READ: Want more babies? Help couples build stronger marriages first, a commentary

ENCOURAGING MARRIAGES

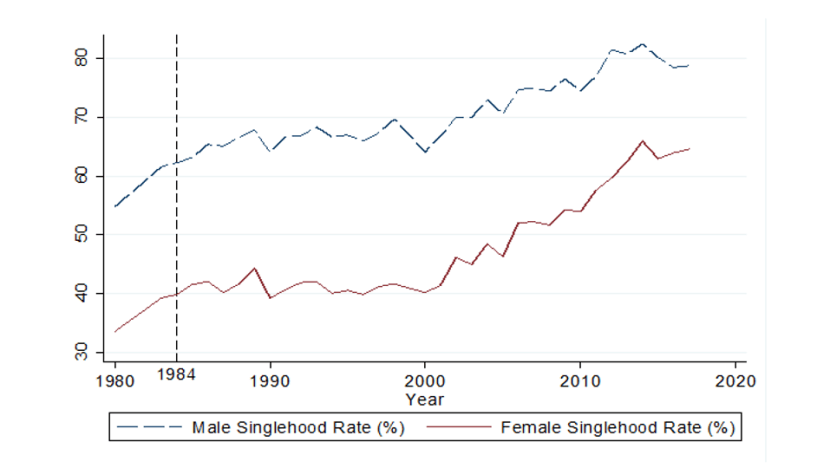

The Government established the Social Development Unit (SDU) in January 1984 to encourage greater social interaction and marriage among graduate singles, on the back of the 1980 population census which revealed an increasing trend of singlehood among graduate women.

Policymakers at the time were concerned of the implications for Singapore’s future talent pool if more well-educated women remained single.

The SDU was conceived to fight this trend by providing opportunities for graduate singles to meet and interact through dinners, outings and other events and reducing the costs of searching for a life partner.

Since 1984, SDU has undergone several changes, including catering to both graduate and non-graduate singles as the renamed Social Development Network.

Though some of its functions have evolved over the years, its primary objective remains to foster interaction and relationship skills among singles to improve the nation’s marriage and birth rates.

DID SDU MISS ITS MARK?

Despite the introduction of SDU in 1984, the trend of singlehood seems to be increasing, leading some to question the effectiveness of SDU and a few calling the scheme a failure.

But it would not be correct to conclude that the SDU has been ineffective based on the rising trend of singlehood alone.

This increase may have been due to other factors such as a greater proportion of women entering the labour market, resulting in more time spent among women at work and less time spent on dating activities.

Indeed, data shows that female participation in the labour market has been on the rise. While the female labour force participation rate in 1980 was only 44.3 per cent, this figure had grown to 60.4 per cent by 2016.

To evaluate whether the SDU had been effective, we would also need to know the counterfactual – that is, what Singapore’s singlehood rates would have been in the years after 1984, had there been no SDU.

Although the percentage of single females in the 25 to 29 age bracket experienced a rise from 40 per cent in 1984 to 64 per cent in 2017, there’s no knowing how this trend may have evolved, had the SDU been absent.

Despite this, it is still possible to estimate the effectiveness of SDU.

One potential low-cost method would be to compare the actual evolution in singlehood rates across two groups of women – unmarried citizens who had completed secondary education who were eligible for the activities organised by SDU (or by the equivalent Social Development Section) and unmarried citizens who had not completed secondary education who were ineligible – before and after 1984.

If SDU’s programmes had a visible effect, we would see the singlehood rates between these two groups plausibly evolving similarly in the years prior to 1984 but then diverging significantly in the period after 1984.

Yet such a study would require access to individual-level birth records and educational attainment data, which is currently only available to selected governmental departments.

STIGMA AGAINST MATCHMAKING ACTIVITIES THE KEY

As the discussion above indicates, more empirical research is needed before we can arrive at a conclusive answer on whether the Government’s social development programmes have been effective.

However, my personal view is that the social development programmes has not been as ineffective as most pessimists might think.

Indeed, the work done by the current Social Development Network (SDN) and its accredited dating agencies – which include matching singles to potential partners based on their profiles and preferences, enabling them to date online, coordination of physical dates, and provision of courses and information to equip singles with the relationship skills needed to hitch a partner – have enormous potential to foster romantic relationships.

These provide singles with access to potential partners they are unlikely to meet over the course of their normal lives and lay the foundational skills necessary for maintaining such relationships.

Much as the process seemed engineered, it’s useful to keep in mind that this was Singapore’s Tinder before the age of dating apps and artificial intelligence.

READ: The age-old currency of modern dating, a commentary

READ: Finding love in Singapore, one swipe at a time, a commentary

The SDN has also since moved into accrediting dating agencies, leveraging the private sector to solve this public problem.

Although we do not have data on how many children or couples got hitched because of SDN, dating agencies accredited by the SDN have reported that more men are participating in these events.

But not everyone eligible for the SDN programme is making use of it. Part of the reason might be the social stigma involved in participation.

People fear that they will be perceived by others as “unwanted” and “undesirable” if they have to resort to matchmaking. The pool of singles engaged in the SDN programme inevitably shrinks this way, so that the number of marriages which form as a result of the programme is not as large as it could potentially be.

The key is therefore to ensure that singles buy-in to the idea of such activities and do not see involvement in these activities as a social stigma. One approach to this is through public education and advertising, to shift mindsets and normalise the search for a life partner, even before people hit the eligibility age of 20.

This way, people are less likely to be misinformed by negative stereotypes and will have a more positive picture of what the network can do for them.

REMOVING AGE RESTRICTIONS IN ACTIVITIES

Another way SDN can extend its outreach is by not limiting its activities to certain age groups. Currently, some activities stipulate an age restriction. One such event on the agency’s website for a dinner date imposed an age restriction requiring participating males to be 32 to 45 and females aged 22 to 35 to participate.

While these age restrictions may be motivated by certain economic considerations and preferences, they are ironic given that they preclude older females, who are the most likely group to be actively seeking a long-term partner.

It might be useful for policymakers to undertake a rigorous study that considers behavioural science, economic and social factors to figure out how best to nudge singles, and determine how well our social development programmes have been doing, as well as how the SDN can benefit more singles going forward.

Until such an exercise it done, it would be premature to label our social development efforts unsuccessful.

Kelvin Seah Kah Cheng is a lecturer in the Department of Economics, National University of Singapore and a Research Affiliate at the Institute of Labour Economics in Bonn, Germany.