From ports in India to visa agencies in China, hopes rising over thawing ties as Modi visits

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi will be in China from Aug 31 to attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in Tianjin, where he is expected to meet Chinese President Xi Jinping for bilateral talks.

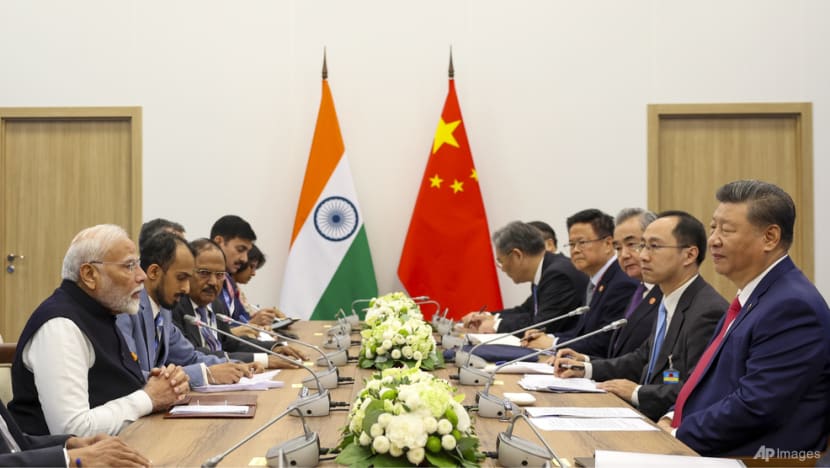

Xi Jinping shakes hands with Narendra Modi on the sidelines of the BRICS Summit in Kazan, Russia. (Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, on X via AP)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SHANGHAI: In early 2021, Vigneswara Vijayaram was watching a shipment of industrial pumps - worth more than US$200,000 - sit idle at Chennai Port. The machinery - imported from China - was critical to an infrastructure project backed by his firm, Portcity Impex.

Nearly a month went by. The cargo never moved. “Additional checks,” officials told him - new layers of scrutiny introduced after the 2020 Galwan Valley clash, which had sent relations between India and China into a tailspin.

“(It) forced us to halt an entire project,” recalled Vijayaram, who is managing partner at the import-export company based in Thoothukudi, a port city in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu.

“After the border tensions in 2020, our cargo shipments - especially machinery and electronic components from China - often got held up at Indian ports for extra inspections, sometimes for weeks.”

No explanation. No timeline. Just the slow drag of post-Galwan chill choking the arteries of trade between the two economies. And for those caught in the middle of that freeze, the memory is sharp.

“It was a period of uncertainty where both sides were wary, and trade slowed dramatically,” said Vijayaram.

As Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi prepares for his first visit to China in seven years - and his first since the border clashes five years ago - business owners like Vijayaram are once again watching both the ports and the politics.

The visit, scheduled for this Sunday (Aug 31) at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in Tianjin, is being framed as a diplomatic reset by observers, with Modi expected to meet Chinese President Xi Jinping for bilateral talks.

But behind the photo opportunities, a deeper question remains: is the thaw real - and can it last?

A FREEZE OF TRUST AND THE SIGNS FORWARD

The Galwan Valley clashes of June 2020 pushed China-India relations into what many observers described as their deepest freeze in decades.

At least 20 Indian soldiers died while China reportedly lost four of their own. They were the first fatalities along the 3,440-kilometre Line of Actual Control (LAC) in 45 years - breaking a longstanding assumption that the disputed frontier was effectively managed.

Dialogue stalled. Direct flights never resumed. Visas were frozen. After the clashes, India banned TikTok and more than 200 other Chinese apps, while Chinese investment came under sweeping scrutiny. The mistrust reached well beyond politics.

“If I look back at the last five years, the most enduring damage isn’t just economic or technological - it’s the trust deficit,” said Srinivasan Balakrishnan, a professor and director of Strategic Engagements & Partnerships at the Indic Researchers Forum.

“Tech was the first casualty, with Chinese apps banned and investments scrutinised, but the chill went deeper. Infrastructure projects slowed, joint research in academia quietly withered, and even Track II exchanges lost momentum,” he added.

Track II diplomacy refers to informal dialogues between academics, retired officials, business leaders and civil society actors from both countries. These forums allow space for idea exchange, confidence-building and problem-solving outside the political glare.

Manoj Kewalramani, head of Indo-Pacific studies at Takshashila Institution, a think tank and public policy school in Bangalore, echoed this view, saying the biggest damage had been the “complete erosion of trust” on both sides. “Not just politically, but also in public image,” he told CNA.

“Rebuilding that is not going to happen with one meeting or two meetings or one summit,” he added.

“It is going to be a long-term task of sustained engagement and peaceful management of the relationship.”

China’s Xi and India’s Modi most recently met on the sidelines of the BRICS Summit in Kazan, Russia, last October, where they endorsed a border disengagement agreement that allowed troop withdrawals and restored pre‑2020 patrolling checks.

In June, China allowed Indian pilgrims into Tibet to travel to sacred sites while India later announced that it would start reissuing tourist visas for Chinese nationals and resume direct flights between Indian and Chinese cities, which had been suspended since the start of the pandemic. China lifted tourist visa restrictions for Indian nationals in March.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s official visit to New Delhi on Aug 18 marked the 24th round of border talks, which analysts deemed the first progress in years.

“This is probably the most substantive dialogue that we’ve seen for the past seven to eight years,” Kewalramani said.

“There are some clear, actionable outcomes … particularly setting up an expert group under the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on India–China Border Affairs to talk about boundary delimitation.

“To me, this is forward movement.”

According to the Chinese readout, both sides have “agreed that a stable, cooperative and forward-looking bilateral relationship is in their mutual interest to realise their development potential fully”.

The Globevisa Group, a leading immigration consultancy with offices in Singapore, Hong Kong and London, told CNA that they had been seeing “positive changes” since India restarted tourism visas for Chinese citizens, and is reportedly opening business visas for Chinese executives.

“With the resumption of direct flights and eased visa conditions, willingness to apply has clearly increased, especially for tourism and business,” a representative said.

“As a result, we have received more inquiries from clients in recent weeks,” they said, adding that inquiries were expected to increase further in the coming weeks as flight schedules fully resume.

Yet the recovery is expected to be uneven, if history is any guide - whether after the pandemic or the 2020 Galwan clash.

Public data showed that in 2019, there were around 200,000 visas issued to Chinese citizens visiting India, according to Globevisa Group. By 2024, that number had dropped to just about 2,000.

“Other destinations offering visa-free entry or greater convenience are more attractive, and India has not been actively promoting tourism in China, which further dampens demand,” Globevisa Group said.

In contrast, visas issued to Indian nationals visiting China have been surging. Data showed around 180,000 in 2023, 280,000 in 2024, and as of Apr 9, 2025, already over 85,000.

Globevisa Group has observed “a noticeable increase in Indian clients seeking advice on working in China”, adding that they just received a request from an Indian client last weekend, wanting to open an Indian restaurant in China.

Smoother processes were also a strong sign of warming relations between countries, Globevisa Group said, with procedures becoming more simplified.

“Some steps that previously required multiple in-person visits can now be completed online,” the company said. “Information posted on official websites is also updated more quickly and consistently, which has improved the application experience.”

China-India relations have still come a long way. “We believe demand for China-India exchanges will continue to grow,” the firm said.

“From our daily operations, it is clear this is not a short-term rebound but a steady, long-term deepening of engagement.”

But others say that thaw in relations has yet to filter deeply into society or business.

“The thaw is still more visible at the diplomatic level than in society or business,” said Balakrishnan.

“Wang Yi’s visit and Prime Minister Modi’s upcoming trip do signal intent, but below the government, the gears are still slow to turn.”

“Businesses haven’t yet returned to pre-2020 comfort levels, universities remain hesitant to restart partnerships, and investors are testing the waters cautiously rather than diving in.”

“There are encouraging signs, but real change is still slow to appear in day-to-day trade,” Vijayaram said, adding that there is “genuine optimism” on the ground.

“Diplomacy is improving sentiment for now but businesses are still waiting for consistent, practical changes before they feel a real difference,” Vijayaram said, noting that political shocks could undo trust “overnight”.

TRUMP’S UNEXPECTED ROLE

As India and China slowly rebuild ties, analysts have pointed to the shifting global landscape - with US President Donald Trump’s punishing tariff policies playing a role in bringing the nuclear-armed neighbours closer.

“In my view, the deeper cause behind the changes in China-India relations is still the shift in the overall international environment,” said Zhang Jiadong, director of the South Asian Studies Centre at Fudan University, who argued that turbulence from Washington was the main accelerant.

“Global uncertainty has clearly risen, and the boundaries between different camps and blocs have shown a clear trend toward blurring,” Zhang said.

Amit Ranjan, a research fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS) at the National University of Singapore (NUS), told CNA that the “motivating factor” was “Trump and his tariffs”.

Trump hit India with an additional 25 per cent tariff over its purchases of Russian oil, raising the total tariff on Indian imports to the US to 50 per cent - among the highest rates imposed by Washington. The new rate came into effect on Aug 27.

“India and the US built ties for a long time,” Ranjan said. “(And then) Trump imposed 50 per cent tariffs - which is not what you’d expect from a friend.”

“This (puts) the Indian economy in a very difficult position and pushes India to warm up ties with China,” he said. “It’s an imbalance created by tariffs.”

In the business world, rising US tariffs on Indian exports have increased costs and created uncertainty, making some companies cautious about relying too heavily on that market, noted Vijayaram of Portcity Impex.

“Businesses see the US as a valuable but increasingly costly market, while China, despite political tensions, continues to be viewed as a dependable manufacturing hub,” he said.

“On the other hand, China still offers scale, competitive pricing, and fast delivery that few other countries can match, even though politics make it sensitive,” he said, adding that many businesses are also “actively exploring alternatives in Vietnam, Indonesia, and domestic sourcing to avoid putting all their eggs in one basket”.

Many of his peers, Vijayaram noted, take a hedged approach: “use China for efficiency, the US for opportunity, and diversify to manage risks”.

But Kewalramani warned against overstating Washington’s role in bringing China and India closer together. “I don't think (the warming ties) are necessarily driven by Trump’s policies,” he said.

“The US still remains one of India’s most important partners. At the same time, China is a geographical neighbour, it is one of India’s largest trading partners.”

“It is a reality that we live with, and we have lived with each other for thousands of years. So until the earth and tectonic plates shift, India and China will remain neighbours. So we have to find a way for each other to get along,” he added.

India-China bilateral trade dipped from US$92.8 billion in 2019 to US$87.6 billion in 2020.

But it recovered strongly to US$125.6 billion the next year and has remained robust since, hitting US$138.5 billion last year.

MODI IN CHINA: HIGH STAKES, LOW EXPECTATIONS

Observers say the Xi-Modi interactions will be among the most closely watched at Sunday’s SCO summit in Tianjin.

“Modi's presence at the SCO Summit is important, but more than (that) is his talks with Xi Jinping. The two countries may take some significant steps to improve their ties,” said NUS’ Ranjan.

The Indian leader’s last visit to China was in 2018 for the SCO summit.

Kewalramani does not expect any major announcements between Modi and Xi. “If something was to be expected, I would probably expect something around people-centric issues around air connectivity and visas.”

Fudan University’s Zhang is managing expectations too.

“The fact that (Modi) is coming at all (to the SCO) is already an important breakthrough in China-India relations,” he said, adding that any major bilateral breakthroughs would be unlikely.

The Indian prime minister will not stay on to attend China’s World War II victory parade, which will be held in Beijing on Sep 3 to mark Japan’s formal surrender in the Second World War - a decision that underscores the delicacy of India’s balancing act.

Modi will be in Japan on Aug 29 and 30 to participate in the India-Japan Annual Summit.

Analysts say the absence is unlikely to upset Beijing, particularly with Modi confirmed to attend the SCO summit in Tianjin.

“Politically, India may not want to take that chance by attending (the parade) due to its historical ties with Japan,” said Ranjan.

“At the same time, (India views) Japan as a more dependable and reliable partner than Beijing,” he said, adding that India and Japan are also part of the QUAD grouping.

“But what matters is that India and China are still trying to get closer.”

Meanwhile, underlying strategic concerns continue to shape the broader China-India relationship.

Maritime tensions could be a future source of conflict, analysts say, pointing to parallel build-ups from both sides in the seas.

China has been heavily investing in South Asian ports like Gwadar in Pakistan and Hambantota in Sri Lanka - what some analysts describe as the “String of Pearls” strategy, aimed at establishing a network of ports and naval bases across the Indian Ocean to extend its maritime influence.

On the other hand, analysts note that India has been developing Chabahar Port in Iran as a strategic counter to China’s Gwadar and has gained access to bases like Duqm in Oman, and enhanced its multilateral maritime cooperation through QUAD naval drills with the US, Japan, and Australia.

“The sea is the future, the new growth point of economic and strategic competition,” Zhang said.

“Two rising maritime powers without necessary communication mechanisms - that is dangerous.”

Terrorism would be another pressing issue for both nations at the SCO, said Kewalramani.

“India clearly sees terrorism and cross-border terrorism from Pakistan as one of its fundamental challenges while China has a very deep security relationship with Pakistan,” he said.

Notably, at the SCO defence ministers’ meeting in Qingdao in June 2025, India refused to sign the proposed joint statement.

The sticking point was diluted language on terrorism.

The statement omitted reference to the Apr 22 terror attack in Pahalgam, which India linked to Pakistan.

Another important area is people-to-people and cultural exchange.

Zhang from Fudan University said that it may seem soft and intangible at first glance, but it is extremely important in the long term.

"Two great powers cannot build mutual understanding and trust without sufficient scale of exchange," he said.

"Yet governments often focus on short-term goals, less on long-term efforts, because the impact of long-term initiatives usually outlasts political terms. So leaders may not prioritise them."

“Right now, the level of people-to-people exchange between China and India is very low - so low that neither government can be proud of it,” he added.

According to NUS’ Ranjan, if both countries want to cooperate for the long term, “the first thing they have to do is start to at least address the smaller issues (before) dealing with bigger ones they have”.

“Unless they do, it will be very difficult for them to move on from these issues,” he added.