China on the verge of migration shifts, as cities adapt to changing housing market

From economic growth engine to risk, China is recalibrating its relationship with the property sector as it keeps its economic growth target at around 5 per cent.

In Harbin, a city in northeastern China, high-rise apartments rise alongside a mix of commercial hubs and historic landmarks. (Photo: Tan Peng Guan/CNA)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

HARBIN: In China's northeastern city of Harbin, high-rise apartments have sprung up alongside a mix of commercial hubs and historic landmarks.

For 55-year-old driver Zhao Yuchun, the view is a constant reminder of what could have been – a missed investment opportunity that still weighs on his mind.

His two flats, which he bought in 2018, could have made him a five-figure profit if he sold them as early as 2019.

“If I sold my flats in 2019, I could have sold it for double its price. I bought it at US$560 (per square metre) and could have sold it at US$1,120,” he said.

“But now that’s not the case.”

The investment, which once seemed like a golden opportunity, has now become a lingering regret for Mr Zhao as he recalls a time before when “people used to buy houses to flip, but now no one is buying anymore".

For Mr Zhao and many others, the diminished returns is a harsh awakening, as property has long been seen in China as an investment that could never fail.

GUARANTEED INVESTMENT NO LONGER

During the housing boom that began two decades ago, more than half of wealth creation came from the appreciation of housing prices.

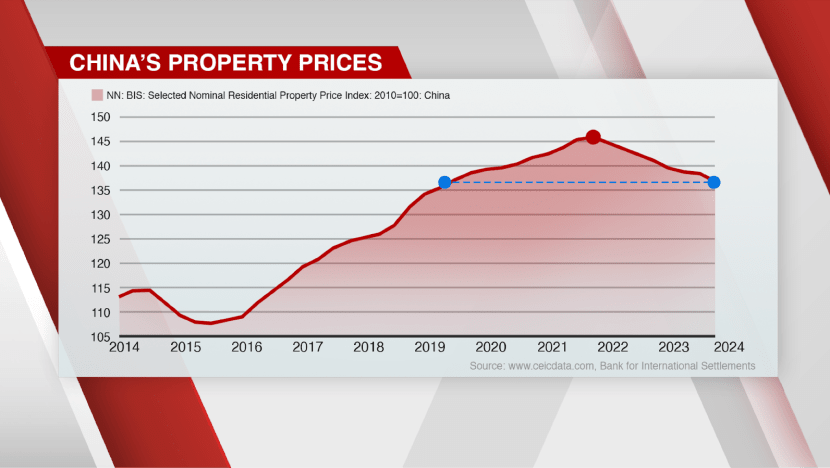

But home prices peaked in 2021 and have since dipped to mid-2019 levels, leaving those who bought at the peak stuck with properties worth much less.

With property making up 70 per cent of household wealth on average, it is a significant blow to people’s spending power and the long-held belief in property as a guaranteed investment.

Housing is also not just deeply tied to intergenerational wealth, said observers.

In most cases, it is also a precondition for marriage, prompting parents to pour their life savings into preparing so-called marriage homes for their children.

Mr Qu Yunlong, a branch manager at Jiaoyang Real Estate, one of Harbin’s biggest real estate firms, said many young people rely on their parents for financial support when it comes to buying a flat.

“Some people don’t have a strong financial foundation, especially those who have just gotten married and need to buy a home,” he added.

But given the current downturn, Mr Qu said “they will have to consider and hesitate” as they contemplate monthly mortgage payments and “if their salary is enough".

Research fellow Zhou Na from the National University of Singapore's East Asia Institute noted: "The younger generations are increasingly burdened by the high housing prices and they are also facing stagnant wages."

She added that this has led them to question the narrative and the symbolism of home ownership, not just as a financial asset but as a cornerstone of marriage, education prospects and intergenerational wealth.

“Particularly when the housing prices in most cities keep dropping after the pandemic, houses seem no longer a good instrument for them to secure family wealth,” she said.

CHANGING PERSPECTIVES

While people born in the 1970s and 80s experienced the housing boom, those born in the 1990s and 2000s had a much more mediocre experience, said Associate Professor Laura Wu from Nanyang Technological University’s School of Social Sciences.

This has prompted “different investment decisions” from those of the previous generation, she said.

Having witnessed the generations before them suffer steep losses in the current downturn, some young adults whom CNA spoke to are no longer as bent on owning a home compared with their parents.

“Renting a place to live is actually a very good option now. I don’t think it’s necessary to be fixated on buying a house. Some people may see owning a home as a form of persistence, but I think letting go of that obsession and experiencing other things might actually be better,” a young Harbin resident told CNA.

Another young resident said: “Buying a house is no longer for investment, but to have a sense of belonging in the city.”

She added: “Having a home feels warm, and it's more about enjoying a better environment."

The changing perspective is bad news for authorities who have, in their efforts to prop up the ailing property sector, pledged to increase the supply of government-subsidised homes to meet the needs of young people among other measures.

The housing ministry late last year laid out a slew of moves to boost housing demand and stabilise China’s real estate market.

“Housing demand fundamentally depends on income growth rate and population growth rate. Now, for both indicators, these growth rates are going to be much lower than the previous four decades, so there is no reason to believe it's going to be really high housing price increase in the near future,” said Ms Wu.

REVERSING THE TREND

Still, there are some bright spots.

In China’s first-tier cities, residential property sales continued to climb in January, defying the downturn seen in second- and third-tier cities.

But lower-tier cities are also working to reverse that trend, courting homebuyers from afar with incentives like free metro rides or whispers of job opportunities.

For instance, since last October, state owned enterprise Liangxi urban development group expanded a housing trade-in scheme to allow residents in nearby cities to swap their old flats for new ones in Wuxi, a city just west of Shanghai.

This includes those from neighbouring Nanjing and higher-tiered Shanghai.

Depending on the conditions of their current property, homeowners can exchange it for one or multiple new flats or trade in several for just one.

According to senior property consultant Yi Yayun from real estate firm LC Fine View, up to 30 per cent of their interested customers come from neighbouring cities like Nanjing, Shanghai, Suzhou and Changzhou.

“The trade-in programme gives them an opportunity to achieve their goal of exchanging the old property, as they need a home in Wuxi for their living requirements … These properties could be older buildings, perhaps without an elevator, and the building age could range from 20 to 40 years or even longer,” he said.

PAVING WAY FOR OTHERS TO FOLLOW

Housing trade-in schemes are not new. They have emerged as a solution to clear inventory, after the housing crisis dating back to 2021 saw developers go bust and market confidence shaken.

But Wuxi is the first to take it across cities, following moves by China to allow local government authorities to craft their own incentive plans in September.

Local state media have hailed it as a pioneering initiative, paving the way for others to follow, including those competing for homebuyers looking to move to higher-tier cities in their struggle to navigate the housing crisis.

In Nanning, the capital of Guangxi province in south China and a tier-two city with a population of about 8 million, developers are reaching out to buyers from as far as China’s northeast.

Others have bundled potential job offers with home purchases, or offering perks like a decade of free metro rides.

“Tier-two and tier-three cities are in fact already in competition to attract population, and in particular the young generation or more specifically, people who have purchasing power,” said Ms Wu.

“Because all these local governments need a labour force, need a young population, not only to buy housing but also to contribute to GDP (gross domestic product), contribute to tax revenue. So it’s going to be a competition of tenants of the labour force in the future,” she adds.

But as ideals change and more young people stay on the sidelines, Ms Wu said what lies ahead is “a great transformation in the housing market.”