Why have 2 kids if returns are low? One couple’s story, one big fertility problem for China

As Chinese millennials navigate through family planning, observers highlight on the programme Money Mind how China could try to keep its demographic transition on an even keel.

Married couple “Ren” and “Fu” live and work in Shanghai. They have a nine-year-old son.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SHANGHAI: For Chinese couple Ren and Fu (not their real names) in Shanghai, having a second child is akin to buying a sports car.

Can they afford its RMB1 million to 2 million (S$207,300 to S$414,600) price tag? Yes. But is it necessary? “After some thought, it seems that it’s not,” said the wife Ren, who works in advertising.

“Another factor is that both of us don’t really like children.”

It is more the sacrifices that come with having children, Fu chimed in. “Over the course of nurturing a child, you’re continually giving, and you don’t get much of a return,” the finance industry worker told the programme Money Mind.

“You give your time and money and a lot of capital. … For this investment, one is enough.”

The couple, in their late 30s, got married in 2009 and had a son three years later.

Their sentiments, born of living in a frenetic and expensive metropolis, are not uncommon among China’s young urban dwellers and are a key obstacle to the country’s push to increase its birth rate, cite analysts.

Beijing announced this week that married couples may have three children, up from two, the limit allowed since 2016. Before that, the one-child policy had been in place since 1979 over fears of a population explosion.

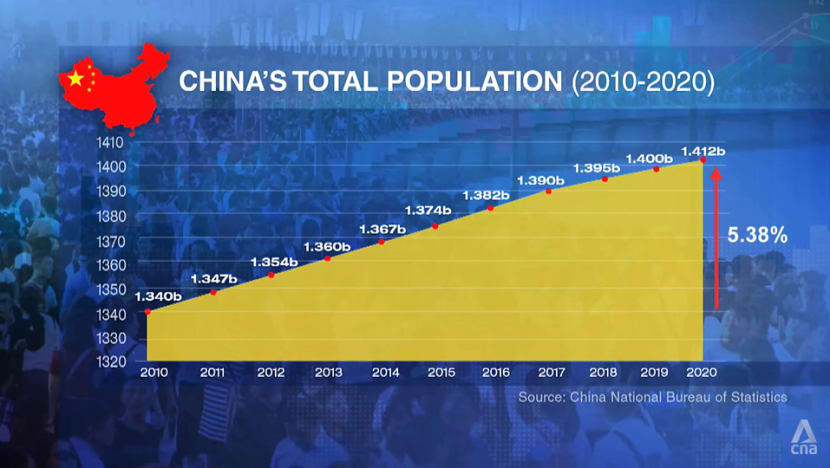

The three-child policy comes after China’s latest census showed that its population had increased by 5.38 per cent over the past decade — the smallest increase since the 1950s — to 1.41 billion.

Its 12 million births last year were also the lowest on record since 1961. The fertility rate was 1.3 children per woman, well below the replacement rate of 2.1.

If the experience of Ren and Fu is any indication, it may be a challenge getting couples to even have a second child.

The one-child policy was still in place when the university sweethearts first met. Soon after they married, couples were allowed to have two children if one party in the marriage was an only child.

While that condition no longer applied later on, Ren said households with more than two children typically belonged either to the uppermost or lowest classes of society.

The wealthiest can hire nannies to care for their children, while the poorest are willing to have more children because they “don’t have much capital”.

WATCH: Why Chinese millennials are stopping at one child — and it’s a problem for China (4:20)

But for middle-income urbanites who work and have parents to look out for, one child is all they have energy for, Ren said.

She and her husband did not plan to have a second child from the start. To do so now would mean “we might have to push back our retirement by 10 years”, she added.

Fu mentioned other considerations, like property prices.

Middle-income families in Shanghai typically live in homes that are less than 100 square metres. At RMB80,000 to RMB100,000 per sq m, they may not be able to afford a larger space to grow their families, he said.

The average entry-level income for Shanghai’s white-collar families is around RMB5,000 to RMB10,000, he cited.

“Another point is the majority of couples in Shanghai are both working,” he added.

“I’m not sure if Singapore has this ‘9-9-6’ saying — that means working from 9am to 9pm for six days (a week). In Shanghai, it could be from 9am to 12am or 1am and for seven days.”

He thinks the Chinese are “not against” having more children, but systemic issues and mindsets stand in the way.

“A bigger part of the problem is how to adjust the economic structure and how to allow people to stay at home more and not keep earning money,” he said.

‘INTERESTING’ CHOICES LIE AHEAD

China’s official Xinhua news agency said the three-child policy will come with measures such as lower educational costs, and more tax and housing support.

Without going into details, it also said Beijing will guarantee the legal interests of working women and clamp down on “sky-high” dowries.

Observers also suggested ways the country could address its population challenges and maintain economic growth: By rethinking its retirement age and the continued development of large cities; tapping technology; and working with small and medium enterprises to raise productivity.

China’s talent pool is deepening as more people graduate from universities. But its “insanely young retirement age” — women at 55 and men at 60 — means a “huge waste of human capital”, said Hang Seng Bank (China) chief economist Wang Dan.

She foresees another “interesting policy debate” in the next five years: Whether the country still wants to focus on developing large cities, where “people tend to have fewer children than in smaller cities and counties”.

“One risk associated with population decline is the housing market in some parts of China, because in the past 20 years, there’s been this build-up of residential housing in many of the mid-sized and small-sized cities,” she told Money Mind.

While the biggest cities are growing, “we’re seeing more and more shrinking regions, especially in the north-east and in the west, so the authorities need to figure out a way to stabilise the housing market in these regions”.

There is also a labour shortage in manufacturing, she noted, although this can be mitigated by robots and greater automation.

Intensifying the use of technology in manufacturing under the Made in China 2025 plan and being a world leader in artificial intelligence by 2030 are already among the country’s goals, cited venture capitalist and Active Creation Capital founder Daniel Tu.

But more vocational schools could be built, and “one obvious area” where investment is needed is the healthcare industry, said Wang.

“China is lacking in its elderly care and healthcare in general, so it could learn so much from countries like Singapore, South Korea and Japan.”

WATCH: The full segment — Demographic time bomb: How will China’s ageing population impact Asia? (6:44)

The next decade may see another economic shift if businesses can cater for single women, she added. Their earning power will “partially compensate the lower consumption due to the low fertility rate”.

Whether China succeeds in raising its birth rate remains to be seen. Ren said the government has already tried to encourage a family-friendly society in some ways.

It set up zones in public places where children can play. It delayed school dismissal timings so that working parents can pick their children up, and does not charge school fees at public schools, she cited.

“No one wishes for the population number to decline, but everyone has their own choice,” she said.

“This is the attitude of the people now: Basically, get married if you find someone suitable; if there’s no one suitable, just stay single. It’s not a big deal — at least in the advertising circle, the culture is very diverse.”

Watch this segment of Money Mind here. New episodes every Saturday at 10.30pm.