IN FOCUS: Singapore confronts emerging threat of far-right extremism

There are currently no known far-right groups operating out of Singapore – the reported cases were all indoctrinated and radicalised online.

Far-right extremism is a threat to Singapore's multicultural and multiracial society. (Illustration: CNA/Rafa Estrada)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: In September 2024, the student walked into a tattoo parlour and asked to be inked on his right elbow.

The design of his choice was a sonnenrad, also known as a sun wheel or black sun – but modified to exclude a black-coloured inner circle. That would be too painful on his elbow joint, the 18-year-old thought.

Still, it didn't take away the sinister symbolism behind the tattoo: The sonnenrad is a hate symbol associated with neo-Nazism.

For Nick Lee Xing Qiu, it pledged his allegiance to the far-right cause, which had inspired him to plan attacks on Malays and Muslims in Singapore.

Lee was detained by authorities three months later.

His was the third case of far-right extremism dealt with under Singapore's Internal Security Act (ISA) in the last four years.

It follows an emerging trend around the world, especially in Western countries, where younger digital natives are targeted.

In Singapore, far-right extremism is a particular threat to its multicultural and multiracial makeup, analysts told CNA.

They also drew parallels between the indoctrination processes for both far-right and Islamic extremism - indicating the potential for Singapore to adapt its established rehabilitation regime for the latter group, to counter the new challenge at hand.

WHAT IS FAR-RIGHT EXTREMISM?

In its annual terrorism threat assessment, Singapore's Internal Security Department (ISD) described far-right extremism as a fast-evolving security threat in countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia and in Europe.

It encompasses a wide range of beliefs that are often exclusivist - seeing other beliefs as incorrect or invalid - and which advocate violence as a way to safeguard ethnic purity or achieve political objectives.

The ISD report noted far-extremism as often conflated with white supremacy, but in fact also containing broader messages of ethno-religious chauvinism or superiority, nationalism and nativism.

The US in particular has witnessed a surge in white Christian nationalism - combining religious and racial elements - in tandem with Donald Trump's return to the White House, said dean of the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies think-tank Kumar Ramakrishna.

White Christian nationalism promotes exclusivist “white supremacist assumptions” about the superiority of “white-Christian” culture and its “traditional way of life”, wrote Professor Ramakrishna in a commentary.

Experts noted that far-right politics in the West, as a reaction to liberal democracies, has since spread globally, including to Southeast Asia.

And it's led to extremist examples in Malaysia and Singapore.

In December 2020, a 16-year-old student became the first person to be detained in Singapore for far-right extremism. A Protestant Christian of Indian ethnicity, he had formulated detailed plans to attack Muslims at two mosques with a machete.

He was released in January last year after authorities said he had made good progress in his rehabilitation journey.

Another 16-year-old Singaporean, who identified as a white supremacist and aspired to attack minority groups overseas, was issued a restriction order in November 2023. A Secondary 4 student at the time, he had self-radicalised by online far-right propaganda, and wanted to further the white supremacist cause, even though he was of Chinese ethnicity.

And the third and latest case involved 18-year-old Lee with the sonnenrad tattoo. He identified as an "East Asian supremacist", believing that Chinese, Korean and Japanese ethnicities were superior.

All three teenagers had been influenced by far-right personalities abroad such as Brenton Tarrant, who massacred over 50 Muslims in New Zealand in 2019.

And these are just the cases which have come to light. Underreporting remains a concern, said security analysts.

THE THREAT TO SINGAPORE

Far-right extremism also promotes the idea that in democratic multicultural societies, the ethnic or religious majority must remain politically, economically and socially dominant; and never be "replaced", said Prof Ramakrishna.

This runs counter to Singapore’s secular, multicultural and meritocratic governance philosophy, he added.

The ISD also explained in January last year how far-right ideologies could be adapted to fit the Singaporean landscape: By promoting an "us-versus-them" narrative that can create deep societal divides, amplify prejudices and encourage acts of violence towards minorities or "out-groups".

Mr Kalicharan Veera Singam, a senior analyst also at RSIS, said that while Singapore has had isolated racist and religiously insensitive incidents over the years, these were not driven by ideological motivations.

Far-right extremism thus presents a problematic "ideological threat" which justifies and rationalises racism and other forms of hate, he noted.

Mr Singam said far-right and far-right adjacent sentiments online can be hard to track; and it may be just as tough to identify those who've been radicalised.

Unlike religiously motivated extremism, the far-right strain evolves with greater speed in terms of symbols and iconography used in creating narratives, he added.

“In Southeast Asia, where the threat in its current form is still relatively new, far-right symbols and iconography adapted to local contexts are hard to interpret.”

With no known far-right threat groups based in or operating out of Singapore, the handful of indoctrinated locals were radicalised online, said RSIS professor of security studies Rohan Gunaratna, who pointed to "several thousand" far-right websites and accounts on social media platforms spreading such extremist ideologies.

Through those online platforms, extremist groups recruit for purposes ranging from spreading propaganda and fundraising to participating in attacks, he said.

YOUTH FACTOR

Singapore’s position as an open and digitised society, with most people having access to the internet on their devices, makes it ever easier to encounter far-right extremist chatter.

It’s thus of little surprise that those nabbed in Singapore so far were all from the younger, constantly online generation.

The ISD has said that youths may be more susceptible to far-right ideologies, and gravitate toward the sense of belonging and identity that those movements appear to provide.

At an age where they are seeking meaning and personal significance, young people may be drawn towards any perceived excitement or status that could come from being identified with far-right movements, said Prof Ramakrishna.

This is seen in the US and Europe, for instance, where such groups can appear to be politically emergent and defiantly anti-status quo.

“Such anti-establishment groups seem to stand out from the crowd with their often shocking slogans and behaviour, which some youth may find ‘cool’ and wish to identify with,” he said.

Dr Mohamed Ali, RSIS senior fellow and head of the Religious Rehabilitation Group (RRG), also highlighted the potential role played by personal circumstances.

“We also need to look at the background of the young person. In many cases, there is a sense of maybe resentment or unhappiness. For example, a youth can come from a broken family or family with problems, or be facing problems in school,” he said.

COUNTERING RADICALISATION

Countries around the world have taken steps to try and tackle the specific threat of far-right extremism.

Germany has introduced a 13-point plan allowing authorities to freeze bank accounts and cut funding for extremists, ban their events more easily and stop far-right activists from entering or leaving the country, among others.

In Australia, a ban on Nazi symbols came into force in January last year, making it also a crime to perform the Nazi salute in public.

For Singapore, the primary approach continues to be a wider one targeting all forms of radicalisation - one which starts from the bottom up.

“More than any other government", the country has worked with schoolchildren and youth to build social cohesion, said Prof Gunaratna.

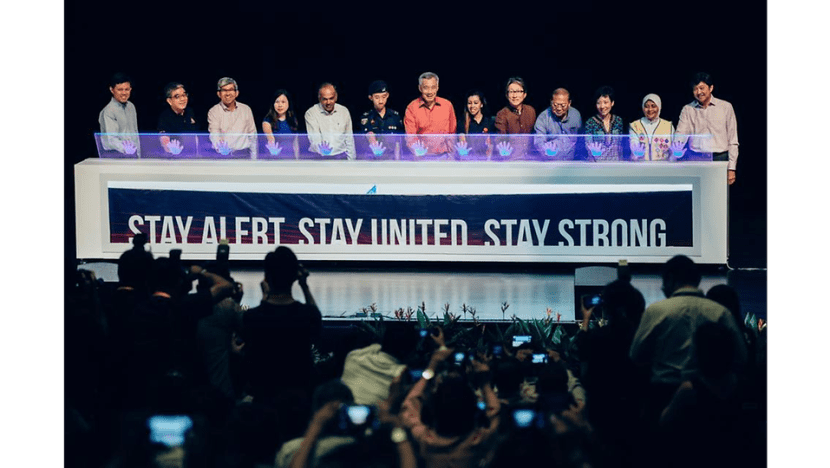

For the population at large, there's the SGSecure movement started in 2016, to prepare Singaporeans to play their parts in preventing and dealing with a terrorist attack.

Outreach programmes by community organisations also help raise awareness of the dangers of radicalisation. These include forums and seminars held by the RRG - a group of volunteer Islamic scholars and teachers.

Then there is the ISA, which among other features allows the Singapore government to detain any imminent threat to the country's security, for up to two years in the first instance.

Since the 9/11 terror attacks in the US in 2001, the Act has mainly been deployed against terrorism.

Prof Gunaratna described it as Singapore's “most effective law” and “an indispensable weapon”.

FIXING DEVIANT THINKING

If the ISA is Singapore's most potent tool in the arsenal, then its secret weapon is rehabilitation.

Analysts said the country is building on its experience of reintegrating Islamic extremists, to develop capabilities to deradicalise far-right extremists, by working with both government and non-government entities.

It has already seen some early success in assembling mentors, educators and counsellors to "mainstream the deviant thinking of the far-right extremists", said Prof Gunaratna, citing the release of the first such individual to be caught here.

Prof Ramakrishna explained that when it comes to identifying the behavioural indicators of far-right extremism, “in many ways it is a mirror image" of radicalisation by the likes of the Islamic State and Al Qaeda militant groups.

“Same essential process, if dissimilar ideological content,” he said.

Dr Mohamed said that since his RRG started work on its initial goal to rehabilitate detained Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) terrorists, over 90 per cent of the group have been eventually released and reintegrated back into society. The network is best known for plotting bomb attacks against Singapore in the early 2000s.

As the nature of terrorism and extremism threats evolved over the years, the RRG adjusted its approaches accordingly, to tackle among others the phenomenon of self-radicalisation first picked up in 2007 and with it, a younger demographic of detainees, he said.

The group continues to extend its remit. It played a part in rehabilitating the first far-right extremist detainee - a Christian who wanted to attack Muslims in Singapore.

Dr Mohamed said the RRG first shared with the National Council of Churches its experience in religious counseling over the years.

A Christian pastor then spoke to the youth. The RRG also sent one of its counsellors to address any misunderstandings the 16-year-old had, which might have given rise to his anti-Islamic sentiments.

Noting his Islamic community's role in helping the very individual who wanted to attack people of their faith, Dr Mohamed said the main principle was to reform and guide the boy away from extremism.

"We should see that as the main objective, and not seek retaliation," he said.

"He could have planned terrorist attacks at any other institution, regardless of the place of worship or the religious community targeted.

"But whether a church or mosque is attacked, the entire Singapore is still affected ... it could disrupt the entire foundation of our religious harmony."