China Power: White elephants or lifelines? Southeast Asia weighs Beijing’s investments and intentions

China’s clout in Southeast Asia is powered by billions of dollars poured into infrastructure. As the US turns inward under Trump, how will regional perceptions of Beijing shift? CNA explores in part one of a series on China’s influence.

The stalled Melaka Gateway project was built on reclaimed land along the Malacca Strait. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

MINDANAO/MANILA/MELAKA: Around once a month, 53-year-old Hernani Catahum sneaks into a construction site where a terrace house previously allocated to his family was being built.

His family of four should have traded their makeshift wooden home for a sturdy concrete structure with electricity and water supply years ago.

Instead, all Catahum can do is peer through the smudged windows of the abandoned project.

In 2018, Catahum and about 20 other families in Tagum in the southern Philippine island of Mindanao were informed they would be relocated as part of the government’s plans to build the China-funded Mindanao railway.

Besides new houses, the families were promised money for their land – up to 6 million pesos (US$105,000) per household.

Many of them were pig farmers and, after news of the relocation, gave up animal husbandry in preparation for the move.

The first phase of the 1,544km Mindanao railway, comprising a 100km stretch connecting Tagum, Davao and Digos cities, was slated to be completed in 2022, cutting travel time from three hours to an hour.

Valued at 81.7 billion pesos, it was to be funded by low-interest loans as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

But tensions flared with Beijing from 2023 due to territorial disputes over maritime islands in the South China Sea, and construction of the railway has yet to start.

“We already made plans in our heads – what to do with the space (in our new home). It’s really hard. We are placed in this situation of uncertainty,” Catahum, a village chief who operates a small grocery shop, told CNA.

“Because of this limbo, the sources of income for our people are affected. We not only have to consider money to feed ourselves, but some of us have huge bills, like university expenses for our children,” said Catahum. For instance, he took a high-interest loan to fund his daughter’s education.

China announced its BRI in 2013, a massive infrastructure drive that has involved over 100 countries and been a defining force in Southeast Asia’s landscape.

According to a report by Australian think tank Lowy Institute in March 2024, China plays a major role in 24 of the region's 34 megaprojects valued at US$1 billion or more.

China remains the most influential economic and political-strategic power in Southeast Asia, ahead of the United States by some margin, according to Singapore research organisation ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute’s The State of Southeast Asia 2025 survey published on Apr 3.

But unlike respondents who chose the US, those who chose China were more worried than welcoming of its growing influence in those spheres.

For instance, nearly seven in 10 who said China was the most influential political-strategic power in Southeast Asia said they were worried, while just over three in 10 said they welcomed its influence in this sphere.

ISEAS’ survey polled 2,023 thought leaders across the 10 Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states and, for the first time in seven editions, included perspectives from Timor-Leste.

But responses from Timor-Leste, which is pending formal admission to ASEAN, were not used to calculate average figures for ASEAN in the survey.

This year’s survey found the region picking the US as the preferred partner over China, if forced to choose between the two.

ASEAN’s 10 members were divided in their trust towards China. Trust levels in Laos, Brunei, Thailand and Cambodia exceeded distrust, while the reverse was true in the other six countries.

Among respondents who distrust China, 47.6 per cent believe its economic and military power threatens their countries’ interests and sovereignty.

This view was particularly strong in the Philippines and Vietnam, where “escalating territorial disputes with China in the South China Sea have intensified in recent years”, the survey authors noted.

These mixed sentiments were on full display when CNA visited several ASEAN countries recently to examine the impact of China-linked infrastructure projects on communities – a result, perhaps, of the projects’ varied outcomes.

Some projects in the region have been scrapped, suspended or downsized, like those in the Philippines and, to a smaller extent, Malaysia.

In countries like Indonesia and Laos, some projects have boosted connectivity and helped catalyse economic growth.

SOME PROJECTS IN LIMBO, OR DOWNSIZED

In the Philippines, the Mindanao railway is not the only project in limbo as ties with China sour.

Under previous president Rodrigo Duterte, who governed from 2016 to 2022, the Philippines largely aligned itself with China and cut a series of deals on infrastructure projects.

These included the Mindanao railway, the Subic-Clark freight railway – which links two former US military bases-turned-commercial zones – as well as a proposed long-haul commuter railway in the southern part of the main Luzon island. The projects were valued at more than US$5 billion in total.

Under current president Ferdinand Marcos Junior, the Philippines has realigned with the US and tensions have ratcheted up between Philippine and Chinese coast guard vessels in disputed areas of the South China Sea. Collisions between vessels from both sides were reported last year.

In November 2024, Philippines Transportation Secretary Jaime Bautista was quoted as saying that China “appeared to be no longer interested” to fund these projects and that Manila was looking for other partners. He, however, refuted talk that his country had exited the BRI.

These developments have left the Philippines in a lurch, the country’s former associate justice of its supreme court Antonio Carpio told CNA in Manila.

Carpio, who led negotiations for the Philippines with China on maritime territories, said those who ultimately suffer from construction delays are Filipinos whose lives would improve with better connectivity across key areas of the archipelago.

He claimed China “tricked” the Duterte administration into accepting offers for these projects and, in return, Duterte’s team did not pursue the Philippines’ territorial claims.

“They dangled all these loans to Duterte, billions of dollars in exchange for Duterte being very soft on China in the South China Sea, but (only) less than 5 per cent of their promises materialised. They took President Duterte for a ride,” said Carpio.

On the other end of the negotiating table, analysts told CNA that Beijing’s main objective for initially offering BRI projects to the Philippines was similar to other projects in the region – to expand commercial opportunities for its companies and boost connectivity in the region for trade.

However, they noted that the Philippines, in particular, is of interest because of the country’s historically close relations with the US, and these projects presented an opportunity for Beijing to score political capital over Washington in the region.

“The US has maintained a strong military presence in the Philippines, and China probably saw the infrastructure projects as an open invitation to dip its toes," international relations expert Zdenek Rod told CNA.

“The US would be extremely hawkish on countries pursuing closer ties with China, so at that time under Duterte, Philippines was straddling between both superpowers,” he added.

Political analyst Edmund Tayao, president and chief executive of the think tank Political Economic Elemental Researchers and Strategists, acknowledged that these infrastructural projects could be beneficial to millions of Filipinos.

But he said accepting China’s funding for these projects cannot come at the cost of his country’s claims to the West Philippine Sea, which is the Philippines’ name for areas of the South China Sea that fall within its exclusive economic zone.

“(With regard to) generosity from China, the Philippines government must do its due diligence,” he said.

Elsewhere in the region, Malaysia has seen some China-funded projects being scaled down.

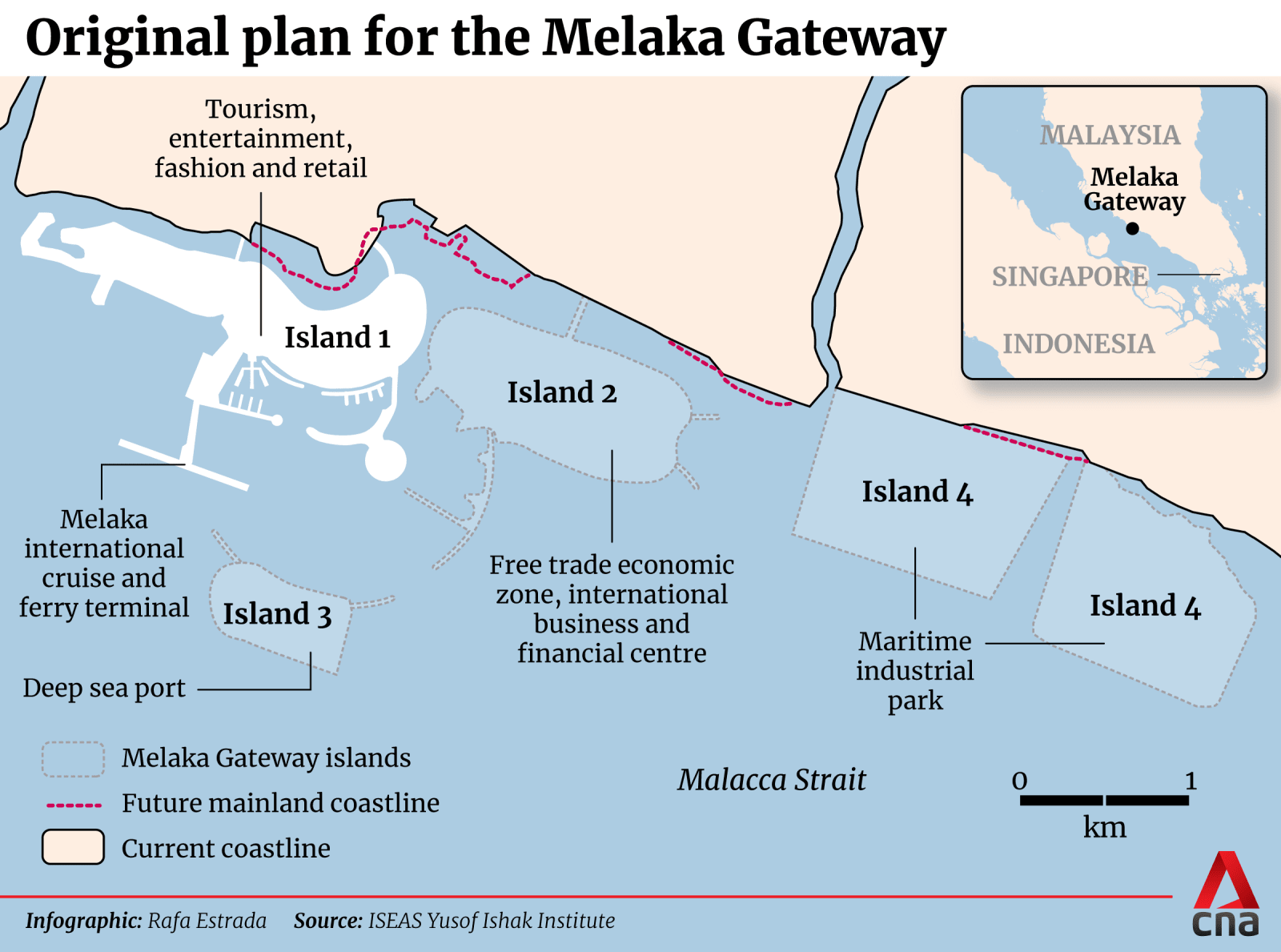

A case in point is the Melaka Gateway project, envisioned as four artificial islands off Melaka city offering residential and commercial developments, tourism activities as well as a port and free trade zone. The entire development was reportedly valued at RM40 billion (US$9.03 billion).

The Melaka Gateway was announced in 2014 under then-prime minister Najib Razak. It was meant to be completed by 2025 but, following legal issues between the project’s developer KAJ Development and the Melaka state government, has been scaled down to an international cruise terminal valued at RM682 million.

The project was said by observers to be part of the BRI as China was aggressively investing in ports and had proposed partnerships with government-linked firms such as PowerChina International and Rizhao Port Group.

Since 2014, a local ethnic Portuguese community of fishermen led by Martin Theseira have repeatedly protested against the Melaka Gateway, claiming that the land reclamation has depleted their catch and caused environmental degradation.

Theseira claimed that even though the project has been downsized, the damage has been done as reclamation work had already begun on the four islands.

“The (Melaka) Gateway has always been branded as the white elephant project,” Theseira said during an interview adjacent to the project's construction site.

“The community is not against development, but not at the expense of the coastal population and ... the environment.”

He also voiced concerns over plans for the project to be partly China-funded, given the Strait of Malacca is a key channel for international trade. The position of the Melaka Gateway could compromise Malaysia’s security along a key trade route, he felt.

“I feel it’s quite dangerous because if they … take over certain portions of the country’s infrastructure, ports and in times of untoward circumstances, what is going to happen?” Theseira opined.

RAIL PROJECTS BENEFIT FROM CHINESE TECHNOLOGY

Some experts are more sanguine about China’s intentions, saying the BRI is part of economic diplomacy.

“A lot of initiatives from China are commercial. That means China wants to make money, in plain language,” said economist Tham Siew Yean, who is professor emeritus at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

In Malaysia, she explained that China views the new East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) as the project set to reap commercial returns, rather than projects like the Melaka Gateway, which have triggered backlash from some sections of the local community.

The ECRL, a 665-kilometre line with 20 stations across Selangor, Pahang, Terengganu and Kelantan, aims to improve domestic connectivity for both passengers and goods. It is set to reduce the travelling time from Gombak, near Kuala Lumpur, to Kota Bharu from at least seven hours by car to four hours by train.

“(Malaysia can benefit from) using Chinese technology in the construction of railway lines, of which we know they have superior technology. It's funded by the federal government taking on a loan (from China’s Export-Import Bank),” she added.

A recent four-part series by CNA explored how the ECRL – expected to start operating in January 2027 – could spur a facelift of the heavily industrial areas surrounding the ports of Klang and Kuantan, alleviate road congestion and better connect east coast towns.

China-funded rail projects elsewhere in ASEAN have been well-received.

The Jakarta-Bandung high-speed rail has been lauded as a strategic economic win for both Indonesia and China. The US$7.2 billion line was 75 per cent-funded by a loan from China and 25 per cent-funded by Indonesian and Chinese shareholders.

The bullet train can run at speeds of up to 350 kilometres per hour, cutting travel between the two cities to just 45 minutes instead of three hours by the regular train.

Locals have also praised how the project has improved their lives by connecting them to loved ones.

Jakarta-based entrepreneur Dimas Bono, who visits Bandung every two months to see his family, has used the rail service more than 10 times since it was launched in October 2023.

“I like it. It’s quick. And it’s also available every hour,” said the 43-year-old. “If you have an urgent matter, it makes your travel faster.”

Dimas is unperturbed by the fact that the HSR was funded by low-interest loans from China.

“Any project from any country, if it provides good and comfortable services for Indonesians, especially services in the transportation sector, we should embrace,” Dimas said.

On top of improving the travel experience, Indonesia’s State Owned Enterprises Minister Erick Thohir said the train line, by using energy more efficiently, has saved the government trillions of rupiah in fuel costs since it began commercial operations in October 2023.

The US$5.9 billion Laos-China railway connecting Vientiane and Kunming has also earned plaudits since it began operations in December 2021.

Over the first 10 months of 2024, it transported a total of three million passengers, marking a 44.4 per cent increase in passenger volume compared to the previous year, according to local daily Laotian Times.

This figure, which averages around 10,000 passengers daily, includes 2.89 million domestic travellers and 107,000 cross-border passengers.

The railway is 60 per cent-funded by debt financing from the Export-Import Bank of China, and the remainder by a joint venture company between the two countries in which China holds a 70 per cent stake.

Analysts said that these projects indicate China’s willingness to collaborate with countries in Southeast Asia and improve the lives of locals, while boosting its commercial interests.

They added that this is part of China’s strategy to gain an edge in the trade war with the US.

Filipino security analyst Rommel Banlaoi, who is also chairman of the Philippine Institute for Peace, Violence and Terrorism Research, told CNA: “China has this policy of prosper thy neighbour. So China will not … take advantage of its neighbours, because without (their support), China cannot also survive in this anarchic world.”

ARE SOME PROJECTS DEBT TRAPS?

Not all observers are as optimistic as Banlaoi.

Although some Southeast Asian countries have benefited from China’s BRI, critics have flagged the risk of a “debt trap”.

This is when countries take on unsustainable loans for infrastructure projects, such that when they experience financial difficulty, Beijing takes over the asset, thereby extending its strategic reach.

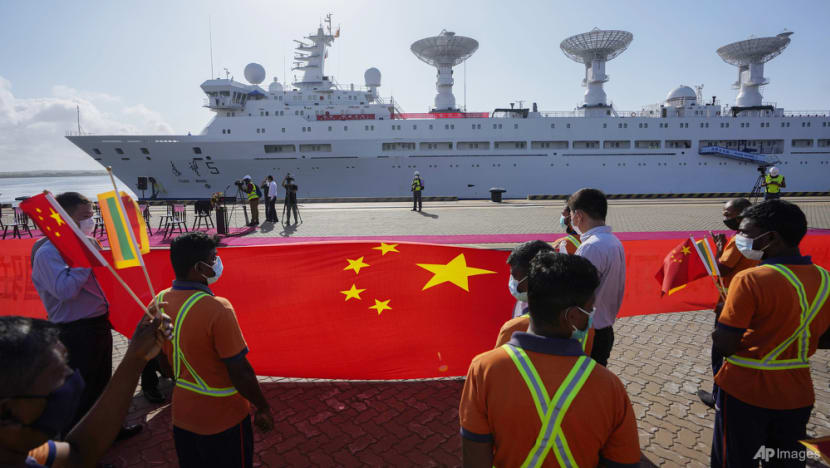

Observers have cited “debt trap diplomacy” playing out in Sri Lanka when China lent money to build the Hambantota port on its southern coast. Struggling to repay its debt, Sri Lanka handed the port over to a Chinese government-linked company on a 99-year lease.

However, Sri Lanka’s leaders have dismissed the notion of “debt trap diplomacy”, with academics suggesting that Sri Lanka’s economic crisis was the more pressing issue.

On the other hand, experts CNA spoke to have warned of the risk Southeast Asian countries face when agreeing to infrastructural deals with Beijing.

For instance, analysts have noted that the cost of the Laos-China railway amounted to one-third of Laos’ gross domestic product in 2019, with US$1.54 billion of the debt incurred guaranteed by the Laotian government. They added that BRI projects like the railway have increased Laos’ external debt.

Researcher Rod, who specialises in the impact of China’s investments on the global economy, said countries like Laos and Malaysia are at risk of falling into a debt trap.

He cited how the Laos government has borrowed around US$6.7 billion in total from Chinese creditors for projects like the Lao-China railway as well as hydropower plants.

In 2020, amid discussions to restructure its debt, China acquired a 90 per cent stake in Électricité du Laos Transmission Company, responsible for Laos’ electricity grid.

“In this case, basically the Laotian government gave it up to them … and foreign actors now have control over critical infrastructure,” Rod told CNA.

“So basically China can control the prices and turn the lights off; they are able to wield this power,” added the assistant professor at the CEVRO University in the Czech Republic.

Malaysia had also found itself entangled with China through the construction of the ECRL, Rod added.

During former Malaysian prime minister Najib Razak’s criminal trial in 2019, a former aide testified Najib had offered infrastructure projects to Beijing in exchange for help to resolve debts incurred in the 1MDB scandal.

The Mahathir government reportedly investigated if Beijing-backed infrastructure projects were inflated due to links to 1MDB debt.

Other experts argue there is evidence to indicate that Southeast Asian countries have agency to negotiate with China and safeguard their national interests.

In the case of Malaysia, they pointed out that after the fall of Najib’s government, Malaysia renegotiated the terms of the ECRL, reducing project costs.

Under the revised agreement, the railway will be operated and maintained by a joint Chinese-Malaysian venture, with each side holding a 50 per cent stake, preventing China from having majority control.

In the case of the Jakarta-Bandung HSR, Indonesia used its state budget to cover the spiraling cost overruns, which analysts say was a sign of its intent to maintain its agency.

Malaysian economist Tham rubbished the notion that China leans on debt diplomacy and said Southeast Asian countries are unlikely to be “beholden to China” through these infrastructural projects.

“Given Chinese investment, does it make Laos … (or) Malaysia beholden to the Chinese government? I don’t see (them) as being subservient to China,” added Tham.

She explained that Malaysia is negotiating territorial claims in the South China Sea with China, but that its strategy is to do so quietly and behind the scenes. It has not forgotten these claims as a result of China funding infrastructure projects, she said.

“As I understand it, Malaysia's way of dealing with the South China Sea is actually to negotiate quietly and not to have an open conflict,” she added.

ASEAN LIKELY TO PRESS ON WITH CHINA COLLABORATION

All in all, there is a sense that many countries would prefer collaboration with China on infrastructural projects even as the US, under President Donald Trump, has pledged to forge more deals to counter China’s BRI.

In late February, Trump’s secretary of state Marco Rubio reportedly said the BRI would “threaten” US interests and lead to China dominating its trade partners, and that Trump was looking to reverse this.

“It is not in our interest to live in a world, particularly in a hemisphere we call home, surrounded by countries that have taken on loans and debt from China that put them at China’s mercy,” Rubio reportedly said.

Political analyst Oh Ei Sun, senior fellow at the Singapore Institute of International Affairs, told CNA that China has a stronger track record in developing infrastructure in the region compared to the US, and is the superpower more likely to garner trust and goodwill.

“Moreover, as most Southeast Asian nations are still (having fiscal issues), they welcome any form of investment and are not in a position to pick and choose. They have no cards to play,” said Oh.

Indonesia is, for instance, in talks with China to extend its high-speed rail network to connect Jakarta and Surabaya.

“Almost all the countries in ASEAN will press on with infrastructural collaboration with China, with the exception of the Philippines,” he added.

Yet, in spite of Rubio’s recent comments, Oh maintained that the US, with its current protectionist stance under Trump, is unlikely to invest in overseas projects. This might lead more people in the region to view China “favourably” moving forward.

“Countries in Southeast Asia (will be more) receptive to high-tech from China as they hope they can be uplifted both quantitatively and qualitatively from their current socioeconomic conditions,” he added.

China has also reportedly pivoted to more modest financing for the BRI.

In late 2023, it pledged 780 billion yuan (US$106.6 billion) in new financing for the Belt and Road Initiative – a modest figure compared to previous years, observers noted.

Grace Stanhope, a research associate with the Lowy Institute’s Indo-Pacific Development Centre, told CNA this signals a pivot from costly huge megaprojects like railway lines to “small yet smart” projects such as schools and hospitals.

“They're using a lot less debt than they were back in the pre-2016 era. And now we see fewer Belt and Road projects in Southeast Asia are being signed,” she said.

However, she maintained that the strategy of funding infrastructure in the region is certainly not dead in the water, and something Beijing will press on with, citing how plans for a Vietnam-China railway were finalised in February.

“The infrastructure focus is definitely still there. So it's not gone away, it's not dead,” she said.

Political analyst Lucio Blanco Pitlo III said that although presently bitter relations with China have derailed infrastructure projects and impacted fruit exports and tourism, the Philippines will be a “laggard” if it does not engage China in the economic sphere due to maritime concerns.

“The concern is that the Philippines (will not be) able to benefit from China’s strengths like infrastructure investment, tourism, green technologies, offshore wind, solar and, not to mention, electric vehicle technology,” he said.

Tagum village chief Catahum agrees.

Even though he is frustrated that China has pulled funding for the Mindanao railway and is seen by Filipinos as the antagonist in the maritime dispute, he is keen for both countries to put their differences aside and return to the negotiating table for the infrastructure projects.

“We are Filipinos, and our sentiments are with our fellow countrymen. But I think the solution is not just to fight against them. They can discuss it at the negotiating table,” Catahum said.

“We hope our leaders will find a solution to these problems. Let’s engage in dialogue with China,” he said.

Additional reporting by Kiki Siregar